By Stella Rithara, Elizabeth Ng’uono Odalo, Asaph Kinyanjui, Catherine Nelson and Dr Sally Hull

Take Home Messages:

- The APCA-POS tool can be used effectively in routine community hospice care in Kenya, where care is mainly provided by community health workers.

- All the teams gained from ‘uncovering’ needs which were previously unrecognised.

- Patient’s experience of pain, and worry about their condition showed most improvement.

Introduction:

Community health workers (CHWs) are found in many low- and middle-income countries. They form an essential part of healthcare teams, and often stay living in their local communities for long periods of time. (1)

In Kenya CHWs are chosen at community meetings and receive some training from Government sources. Palliative care training is an additional module, and is usually provided by independent hospices, and by the Kenya Hospice and Palliative Care Association (KEHPCA). (2) Hospice care Kenya, a UK based charity, has funded palliative care training for CHWs for over a decade. (3)

Although Kenya is one of only four African countries which includes some palliative care in their health programmes, there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of including CHWs in the delivery of community palliative care. (4)

The African Palliative Care Association-Palliative Outcome Scale (APCA-POS) was the first palliative care outcome measure to be validated in African countries, (5,6) and is widely used in research and clinical settings. It enables quantitative measurement of changes in the symptoms and quality of life of patients, and identifies those aspects of patient and carer well-being best supported by palliative care. (7)

This project aimed to improve the quality of care provided by CHWs to community based palliative patients and their carers, by using the APCA-POS outcome scale during regular care delivery in three areas of Kenya.

Methods:

The project was based at independent community hospices in Siaya county, West Kajiado county and at Nairobi hospice which runs clinics in the urban slums of Nairobi. .

In 2020 the nurses leading the project at each site had training on using the APCA-POS from KEHPCA. This training was rolled out to CHWs, and other hospice staff.

The APCA-POS surveys were filled in at first contact with the patient and their carer, and were repeated one month later.

Results:

Over two years 1,415 patients and 978 carers received community palliative care. The most frequent diagnosis among the patient group was cancer (1,059 cases) followed by HIV/Aids (193 cases), and other chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, chronic kidney disease (163 cases).

12% of patients and 19% of carers received the APCA-POS survey at first contact and one month later after receiving palliative care.

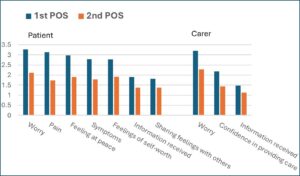

The graph shows there was improvement across multiple domains of care. Overall 82% of patients and 66% of carers showed improvement. The greatest improvements for patients were in the scores for pain and for worry. For carers the greatest improvement in scores was for their worry about the patient’s condition.

Figure. Comparing the average score for each APCA-POS question at baseline, and one month later among 170 patients and 186 primary carers.

Using the APCA-POS at first contact allowed the identification of needs which might otherwise have gone unrecognised, and encouraged conversations to address hidden problems, as illustrated by these examples.

Nicholas, aged >65, a cancer patient.

His first APCA-POS showed a high pain score (question 2, score 5). His pain medication was reviewed and increased. At the second survey, a month later, his pain score had fallen to 1.

Michael, aged 29-45, with colorectal cancer.

The first APCA-POS identified that he had inadequate information about his illness (question 6, score 5). This prompted the hospice staff to discuss his condition, treatment plan and prognosis. At the second survey his score for question 6 had improved to 3.

Patrick, aged over 56 with prostate cancer.

The first APCA-POS survey showed that his wife, his primary carer, was overwhelmed

with worry about the care she had to provide (overall carer score 13). The hospice team

encouraged her to receive counselling, and by the time of the second survey she was

providing care with more confidence. Her overall carer score had fallen to 2.

Discussion:

Following the validation of the APCA-POS in a multi-centre African study in 2010, (8) it has been used extensively in research and hospital settings. It is used less frequently in community and home-based based palliative care, which is often mainly provided by community health workers.

This study demonstrates that a quantitative outcome tool can be used in community settings in Kenya. The benefits are that patient and carer needs can be identified and prioritised. Some needs that may previously have gone undetected, (such as wanting more information, or carer anxiety) are recognised and appropriately responded to.

Although the CHWs said the survey tool was straightforward to use, and the questions were easily understood by patients and their carers, the numbers of completed questionnaire results one month apart remained low. The reasons given for this included adding a further task to an already heavy workload, unfamiliarity with the benefits of using an outcome tool, patients or carers only completing one form, and the additional difficulties imposed by the project running during the Covid pandemic.

The low completion rate of consecutive APCA-POS questionnaires (only 12% of all patients seen) is a weakness of this project. These rates might be improved if enthusiastic senior staff act as role models, and if all team members can see how the early identification and response to problems can improve patient care.

References:

- World Health Organization. What do we know about community health workers? A systematic review of existing reviews. 2020 (Human Resources for Health Observer Series No. 19)

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/what-do-we-know-about-community-health-workers-a-systematic-review-of-existing-reviews - Kenya Hospice and Palliative Care Association

https://kehpca.org/ - Hospice Care Kenya

https://www.hospicecarekenya.com/traininginpalliativecare/ - MacRae MC, Fazal O, O’Donovan J.(2020) Community health workers in palliative care provision in low- income and middle- income countries: a systematic scoping review of the literature.

BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e002368. doi:10.1136/ bmjgh-2020-002368 - Powell RA et al (2007) Development of the APCA African Palliative Outcome Scale.

J Pain and Symptom Manage 32(2) 229–32

DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.008 - Harding R et al (2010) Validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care in Africa – the African Palliative Outcome scale

Health Qual Life Outcomes 8(10) DOI: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-10 - Downing, J., Simon, S.T., Mwangi-Powell, F.N. et al.(2012) Outcomes ‘out of Africa’: the selection and implementation of outcome measures for palliative care in Africa.

BMC Palliat Care11, 1 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-11-1

Authors

Dr Sally Hull (right) training CHVs in the Masai community

Stella Rithara, Kenya Medical Training College

Elizabeth Ng’uono Odalo, Siaya Hospice, Kenya

Asaph Kinyanjui, Nairobi Hospice, Kenya

Catherine Nelson, Hospice Care Kenya

Declaration of interests

We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.