Professor Punita Lal is an oncologist from India. Here, she describes a palliative care placement in the United Kingdom. She spent a month at Velindre Cancer Centre in Wales, where she experienced inpatient, outpatient, community and hospice palliative/supportive care.

Providing comprehensive acute palliative cancer care – many models exist!

Donning different hats is never easy – at least not in oncology! One moment one is an oncologist and the other minute, a palliative care physician. Both have disparate but essential roles to play in cancer care. As an oncologist, one is trained to offer systemic treatments of varying kinds to the patient, respecting a risk-benefit that is often based on available data, but also a gut feeling. With my palliative care physician hat on, cancer directed treatment can sometimes take a back seat, especially if it may make the person worse or even shorten their lives But both roles can exist in harmony, as I have found out.

Broadly, in India we have been doing just that. The same person quite often wears different hats – one of an oncologist and the other of a palliative specialist. At any time point, a doctor is looking at the cancer treatment of the patient and, the very next moment it is all about symptom management, breaking bad news, etc. This model works in India for a variety of reasons – patient numbers are vast. We are therefore constrained by a lack of trained manpower at all times. Required medical care is usually miles away from home, and by the time the patient reaches the hospital he/she may not be in a position to be shuttled across the facility, between two departments. Comprehensive care, all under one roof therefore makes sense. The patient is referred to an oncologist. This treating doctor and the team develop a connection with the patient and those close to them. Once with the patient, the same clinician seamlessly switches roles, delves into the psychosocial aspects as well, converses on sensitive issues like prognostication, nature of illness, intent of treatment, need for comfort care and above all, what lies ahead.

My visit to a facility in the United Kingdom, at the Velindre Cancer Centre, Cardiff, brought out another model of providing palliative cancer care. They have a dedicated palliative & supportive care team for the cancer patients who are either admitted to the hospital or to the hospice, or are at home. In my first few weeks I learned that Wales has two languages, English and Welsh (Cymraeg). ‘Diolch’ means thank you, ‘croeso’ means welcome. Siwan, one of the palliative care nurses worked on my Welsh pronunciation, which was not easy, but we got there!

Here in Velindre University NHS Trust in Cardiff, a referral comes to the palliative team via the oncologists, nurse specialists or allied healthcare professionals, sometimes early on in the illness, even from diagnosis onward. Both the patient and the palliative team become familiar with each other. A big referral point are the daily acute oncology service meetings, where many a cancer [patient will present with numerous symptoms, for instance from spinal cord compression. Apart from the physicians, the specialist nurses are an integral part of the team and routinely and independently provide palliative care to cancer patients. Moreover, they have a strong network with acute assessment unit, community nurse specialists, district nurses, the GPs and the occupational therapist etc. Professor Mark Taubert is the Clinical Director for Velindre’s palliative care services across Cardiff and the Vale region, and leads the overall care provision. The palliative teams are able to ensure that the patient’s basic medical and psychosocial needs are met – whether at home, hospice or at the hospital.

All this information, including the more challenging news, is probably easier to digest by the patient and those who are close to them, when it comes from a familiar and a trusted face. There is continuity of care, since it’s the same person/team which holistically takes care of all the needs. Another reason for the same clinicians to play different roles is that except in a few states like Kerala, specialty nurse training in palliative care is limited in India. There are very few specialised palliative care nurses, who fit the role. The oncologists on the other hand, do acquire the palliative care skill set as a part of their training.

At Velindre, I also got involved in a service that palliative care teams are quite involved in; cancer associated thrombosis (CAT). Professor Nikki Pease, a palliative care consultant at the Velindre Hospital, together with haematologists and a multi-professional team, hold a very special interest in this area. Spending time in her CAT clinic made me realize how much overlap there is with acute oncological and palliative care patients. If vigilant, we may prevent these complications in these advanced malignancies.

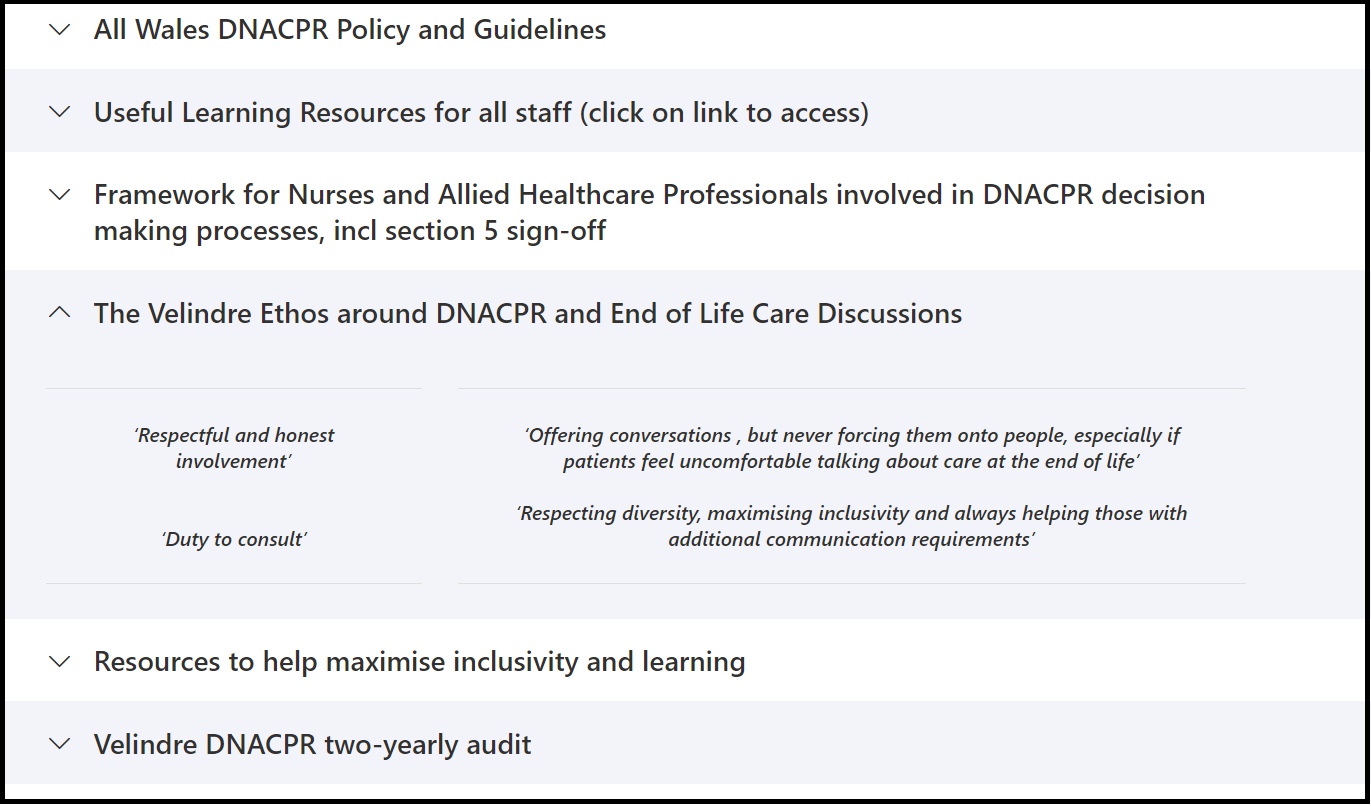

The palliative team at Velindre are often required to delve into advance and future care planning, and hold sensitive conversations with the patient, including about do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR), preferred place(s) of care provision, and other things that matter most to the patient. There is an All Wales DNACPR policy and an enormous amount of training and modules, to teach clinicians (not merely doctors) aspects of communicating this challenging topic with individuals, including the treatment ladder approach. Similarly, should a need arise, the all Wales treatment escalation plan matrix can be discussed with a patient, in line with an all Wales approach to future care planning. This can deal with intensive care unit admissions, intubation, ventilators, during the terminal phase, and aims to give a recommendation to patients, but also explore their views once they are more fully informed. These transparent conversations and this doorstep delivery of supportive care, provide the much-needed continuity of care to all. At the same time, it can reduce hospital admissions that are not wanted by the patient and those close to them.

I was able to witness many conversations, including on Prof. Taubert’s Tuesday palliative care teaching ward round, but also on community visits and in the acute assessment unit. Sometimes, more challenging conversations are pre-announced: “Tomorrow, I may want to discuss with you and your wife what we might do if you get really unwell again, and are less able to express your views, if that’s ok?”

Equally, I was able to join consultants in the community (City Hospice) and also in the Marie Curie hospice in Penarth, both on inpatient ward rounds and seeing how the different professionals work. Speaking to Prof Fiona Rawlinson, who is the lead for the Short Course, Diploma and MSc in Palliative Care at Cardiff University, was informative and enlightening, and the vital importance of (International) palliative care education.

The two other major differences between the Indian and UK practice are need for patient autonomy, and financially, who actually supports the treatment. Patient autonomy is of paramount importance in the UK. The patient has the right to know (and not to know, if he/she so desires). If a DNACPR or treatment escalation decision is required, then clinicians have a duty to consult, and not doing so can be in violation of their human rights (in accordance with article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights, as I learned).

By contrast, in India, the immediate family influences the decision making significantly. There is a degree of collusion between doctors and the families, usually the nominated head of family, sometimes so much so that a patient is not involved in decisions. Although the cancer patient may know of their diagnosis, he/she may understand only the broadest tenets of treatment being offered to him/her. The oncologist cum palliative care physician may address “do not resuscitate” (DNR) discussions in a few of their dying patients, but only with their next of kin: the patient is nearly always kept out of this final part of the conversation. The family’s role is also linked because they usually pay for the treatment, and therefore a lot depends upon their paying capacity. Who pays, decides. This is in sharp contrast to the UK system, where the NHS takes care of all the expenses, and therefore the treatment decisions are mostly based on the actual requirements.

To sum up, the advance & future care planning and palliative cancer care practice in India and the UK are vastly different, and have given me reason to reflect on aspects that I wish to take back with me. Both continue to provide culturally sensitive services in their countries, respecting customs and habits unique to the location, within the confines of what is in the best interests of those affected by life-limiting illness. We have so much to learn from each other, and we should cultivate the culture of learning every day so that those we serve can benefit.

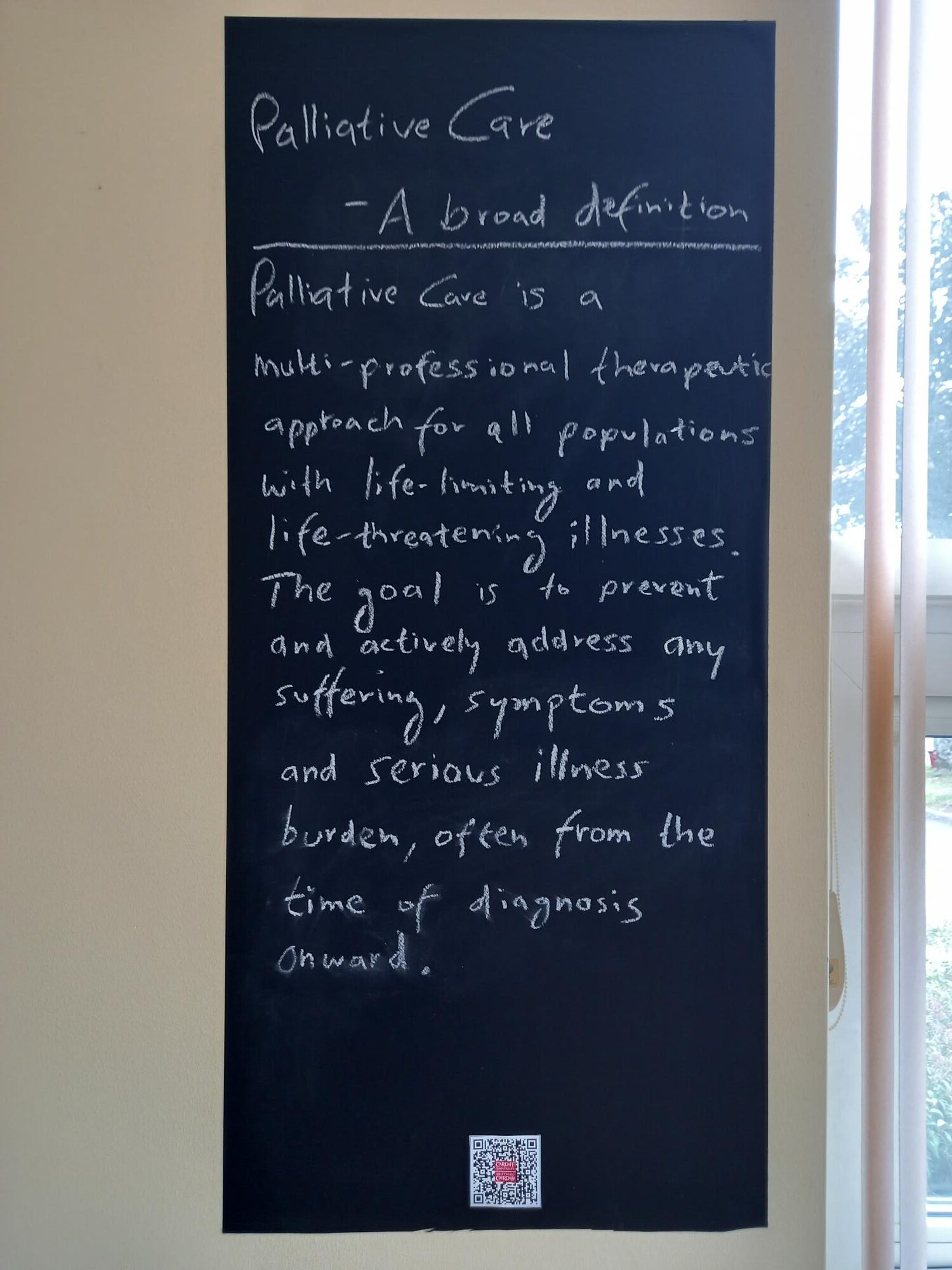

‘Palliative Care is a multi-professional therapeutic approach for all populations with life-limiting and life-threatening illnesses. The goal is to prevent and actively address any suffering, symptoms and serious illness burden, often from the time of diagnosis onward.’ – Velindre University NHS trust definition of palliative care as described in the specialist team’s terms of reference.

Links:

Cardiff University Palliative Care postgraduate courses Youtube video: