I didn’t think it strange, growing up around such a perspective. My mother insisted, when I was preschool age, she would want to die if she were severely disabled. We were at the shopping mall, looking for shoes. She said it as breezily as if asking, “Would you like an ice cream?” True to form, 45 or so years later, dying of Motor Neuron Disease/ALS, she chose to stop eating and drinking. I was in the midst of a PhD program and knew her choices were unusual. I changed my area of study to helping those at end of life die in line with their wishes.

I hearken from a long line of women comfortable with death. I assumed this was part of Judaism, which treats death simply as part of life, with rituals bearing up the bereaved, supporting them and bringing them back into the fold of the living. But not everyone, including my father, were so comfortable. He tried to talk Mom into life-sustaining treatment. She wouldn’t have it. When he realized she was suffering, and adamant, he fully supported her.

My mother often said things about death. “Do what you want after I’m gone,” “What’ll I care, I’ll be dead!” She wrote letters for us to read after she died. “Grieve, my death” she wrote, “but not too much. Life is for the living.”

My research showed mothers might perceive relationships with adult daughter carers in a rosier light than the daughters do. I have two adult daughters myself and try, perhaps to a fault, to keep current with them about “how we are doing emotionally.” I want to avert this pitfall, parents assuming all is well when it’s not. I want to create the best relationship with them I can, through final days.

I talk to them about death too. One purses her lips, steeling herself with a, “Here she goes again,” look. The other—a healthcare provider—is happy to know where my plans are kept on the computer, how to get into the safe, where I keep the cemetery papers, who to call.

I visited the cemetery several times, accompanied by a woman who works at my synagogue, a Native American. She was just as comfortable as I walking the rows, reading headstones, discussing who we knew and liked—even loved—and whom I’d want to be buried near. I chose a shady spot beneath an evergreen, and the next time I saw my to-be-cemetery “neighbor,” I let her know. “See you… forever,” she quipped, rather than “Goodbye” that day.

Next, I consulted the funeral home, telling them what I wanted, paying all the expenses. It’s customary for Jews to be buried, not cremated; to return, dust to dust, in a simple pine box equalizing everyone and deteriorating to earth. Even more traditionally, we are buried on a simple plank, wrapped in an intimate shroud. That’s what I chose.

I was ecstatic leaving the funeral home, knowing my children would not have to figure out details, let alone subsidize them after I’m dead. I wanted to share my excitement, but could only crow to my children (whether they wanted to hear it or not). Anyone else might have thought it, well… weird. But in fact, not talking about death, denying it, is much the stranger custom.

Years ago, a study showed Americans have dozens of euphemisms for death. “Passed away,” “departed,” “succumbed,” “lost their battle,” “entered eternal rest.” The UK—no surprise—is much more literary than America in death euphemisms, with bouncy terms like, “wearing a wooden onesie,” “doing the final moonwalk,” or “ate the pomegranate.” (I’m sure to pause next time I eat that fruit.) Lately, I’ve noticed West Coast hipsters (I dub them this with utmost affection) say someone “transitioned” when they die. I began my career as a nurse-midwife. “Transition” is the worst and most painful part of human labor and birth. I’ve endured labor “transition” four times myself. The term decidedly does not work for me in describing death, despite parallels between birthing and dying.

We all die, obviously. I’m grateful to be comfortable while so many squirm. To visit friends with terminal illness, discussing what they want, how they can facilitate these plans; breaking the stigma around death talk. One word at a time, you might attempt this as well. “Die,” “death,” “dying,” “dead.” These words are easy once you try. And true.

Death, after all, is simply part of life.

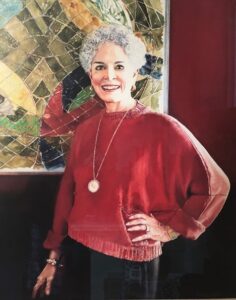

Author

Diane N. Solomon, PhD, PMHNP-BC, CNM (ret.)

Diane N. Solomon, PhD, PMHNP-BC retired from psychiatry in Portland, Oregon to write narrative essays intersecting health, mental health, and well-being. She is an adjunct professor at Oregon Health & Sciences University and an emerita executive committee member of the Oregon Wellness Program, offering free mental healthcare to healthcare professionals in her state. She is also a retired certified nurse-midwife. She writes for Psychology Today and elsewhere, and can be found on X and Instagram.

Declaration of interests

I have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None