By Dr Matthew Doré, palliative care consultant at Northern Ireland Hospice & Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast.

“They have been in hospice for a month,” is the phrase which is sometimes spoken aloud but more often is in thought and generally implies the patient has had their time and should be discharged now.

I want to talk about time and its place in palliative care. Our in-part realisation that there is unproportionable importance to the period of time at end of life and to try and ‘circle the square’ when it comes to resource allocation for such. I want to call this ethos ‘Chronative care’, after the Greek Titan ‘Chronos’, who as the personification of time, understood time as not an aim in itself.

To articulate a palliative care perspective, I would say that ‘time’ is nothing more than a sequencer. It is the events along said timeline which provide the depth and importance in each of our lives, rather than the ‘time’ itself. These events mature and build our character, our memories, adding to ourselves, shape us and become our identity.

These events are what we value and place as important to our lives, and we discuss in fondness (or displeasure) with each other. They are however not regular, rather occur in irregular clusters throughout our life. For example, but certainly not exclusively, there are key events I personally remember, such as my first day at school, or an early Christmas, or my driving test, or my university flat, or my marriage and the births of my children. They are also significant decisions and choices I have made, such as the moment I decided to marry her or buy that house. They are also significant events to others, such as deaths of loved ones, marriages and the good and the bad news we all hear. Conversely there are also periods of perceived less significant or less impactful events whereby I struggle to recollect any particular event, these may be short in time but often are for longer periods.

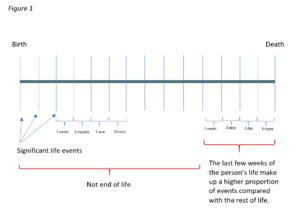

My point is there are a preponderance of events of various intensities at different points in our lives. Day to day the intensity is low, but along the way events happen. Another way to explain it is if we were to take our clusters of events and space them out equally across our timeline, we would see that the spaces in-between each of the events vary from a matter of seconds to many years. I.e. ‘Time’ is relative on our equidistant event life timeline.

This is not to discount day to day life, the beauty in the ordinary. Neither the subconscious events which also shape us, but lack a conscious memory to underpin this model. Rather it is to highlight that the last days, weeks or months has a higher preponderance of significant events in someone’s life, especially for the individual but also those people around them. For example, these last few weeks of life could encompass, the first time you couldn’t get out of bed, insight into your own mortality, saying ‘I love you’, writing letters, saying sorry, resolving old feuds, last time I did x,y or z, and a goodbye kiss. Huge significant events crammed into a tight timeframe.

Returning to our chart of equal distancing of events through a life, I would argue that a greater proportion than we expect of the whole of someone’s life, in terms of events, happens towards the end than that we initially assume. This is like the increased significance of the conclusion of a novel.

Thus, when we perceive someone staying ‘too long’ in hospice care, or ‘they are taking a long time to die’ or indeed the opposite, ‘they died very quickly’. We are looking at it from the perspective of linear time, rather than that of the ‘life events’ timescale. Of course we can’t keep everyone in hospice forever, indeed often it is not the right thing to do and it is arrogant to think it is always the best place, but we can be mindful of the potential life events which don’t go by our notion of time, rather the gap is a bit longer, or shorter. The time of someone dying in hospice having been admitted for 5 minutes and that of 6 weeks is different, but the significance of them could arguably be the same. This concept is hard to explain regarding our resource allocation which can be based around time rather than events.

I suggest, in thinking about events the person has to go through, rather than that of time / prognosis remaining, is a helpful way of thinking for our patients. Those significant events are going to happen, just we need to frame them, highlight them, adjust our care to accommodate them, almost irrespective of time.

Figure 1 demonstrates significant life events, spread out equally across the entirety of a person’s life timeline. This demonstrates the variable time periods in the gaps in-between, but also pictorially shows the ratio of the number of life events are unproportionally weighted towards the end of life.