By Dr Mark Taubert, Consultant in Palliative Medicine, Velindre NHS Trust, Cardiff @DrMarkTaubert

“I have no idea what’s awaiting me, or what will happen when this all ends. “I know that man is capable of great deeds. “But, you know, I feel more fellowship with the defeated than with saints”- Albert Camus

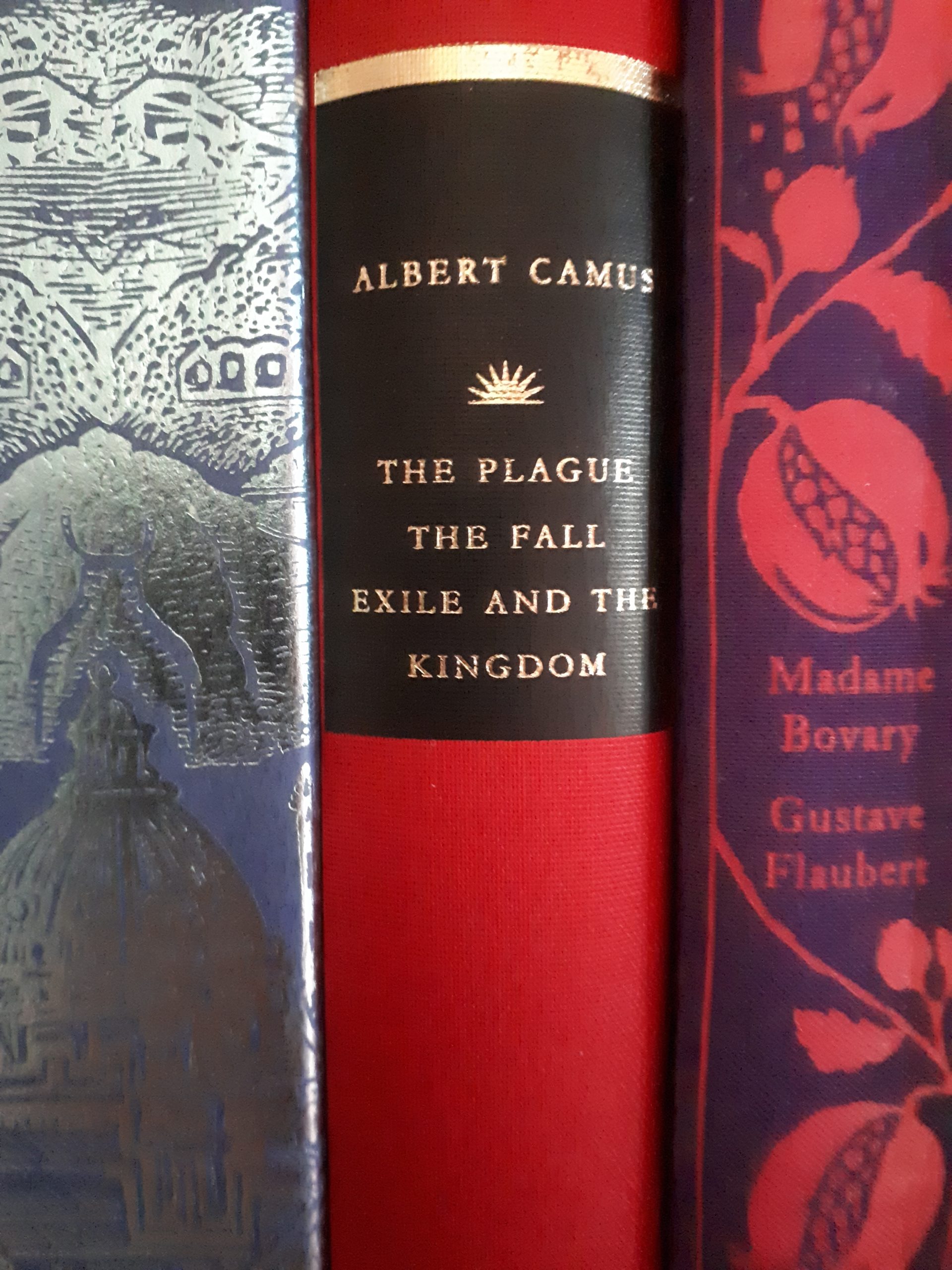

I read The Plague, by Camus, when I was 16. It was part of an assignment for my French class in school, and the warn brown book cover did not look all that inviting at the time. Forced to read it, I soon got engrossed in the fast-paced narrative of doom, which centres around a town called Oran, on the Algerian coast. A town faced with a devastating siege: the bubonic plague.

It was, as I later discovered, a story that I would never forget, and its narrative and protagonists are still with me today, in the midst of the current Covid-19 virus outbreak.

I won’t give too much of the plot away here, but it is a book worth reading, with parallels for our modern world. In revisiting the pages of his book, after a week of working at different hospitals, hospices and attending meetings to prepare for the likely challenging weeks and months of virus outbreak ahead, I found it helpful to sit down and reflect on Camus’ work.

‘Close the town!’

The outbreak starts soon after rats appear around Oran, an occurrence vehemently denied by Tarou, a hotel manager, who is desperate for life to continue as normal. But swiftly, as the bacillus spreads, life comes to a standstill and the town is closed off to the outside world. Lock-down. Self-isolation. Everything changes: the population can no longer enjoy the freedoms and endeavours they had before. A culture of mistrust soon sets in. People become fearful of their neighbour giving them the dreaded disease, or fretful and angry at others not sticking to the imposed special measures.

Different characters and their attempts to deal with the outbreak move into sharper focus. Dr Bernard Rieux is central. His wife, who has been unwell for some time, is in a sanatorium outside the locked-down city. Rieux soon realises the likelihood of an enormous death toll and convinces the town authorities to act. The prefect’s brusque decree to “close the town”, completes the first part of the book. Cottard, who describes himself as a travelling salesman in wine and spirits, but is actually a criminal on the run, is emotionally devastated and broken. Elderly civil servant, Joseph Grand counts the dead, whilst the magistrate, Othon, learns that his son has died from the plague. Then there is the enigmatic figure of the priest, Father Paneloux, a spineless cleric, who is swift to lambaste religious laxity of the people of Oran and adapts his sermons with great adeptness for the direction of the political wind. The journalist Rambert who was merely visiting the town, gets caught up in the plague and tries everything to escape. Jean Tarrou, a former Spanish Republican fighter, sets up a volunteer force to defeat the illness. Tarrou feels that the plague is everybody’s responsibility and that each and everyone should do his or her duty. What interests him, he tells Rieux, is how best to become saintly, even though he does not believe in God.

During the epidemic, Rieux heads an auxiliary hospital and works long hours treating dying patients. He injects serum and lances abscesses, but there is little more that he can do to save his patients, and his duties weigh heavily upon him. He is, by modern descriptions, a pioneering palliative care doctor. Immersed in so much work and long hours, he attempts to distance himself from the natural feeling of pity that he feels for the victims; otherwise, he would not be able to go on.

Coping in times of contagion:

This is a novel about occupation and overcoming. Camus published the novel in 1947 and the town’s sealed city gates embody the borders imposed by the Nazi occupation, while the ethical choices of its inhabitants build a dramatic representation of the different positions taken by the French. But it is more than a critique of a certain part of history, it is, in my view, timeless. How do individuals and groups of people deal with terror, isolation and humiliation. How would you react if your previously comfortable existence is deracinated?

I find myself reflecting on how much like a war novel this is, and whether the way we feel during a disease outbreak, with its restrictions on our movements and ominous foreboding, is perhaps similar to times of occupation in war. The narrative of the doctor’s struggle to palliate the sick, and the different responses of the other protagonists, unleashes an allegory of conflict and battle. Themes like terror, cruelty, selfishness, dying and death, civility, acquiescence and ultimately, alliance, are examined from multiple angles, and dissected in gory detail.

The human faces of an epidemic:

Rieux himself, the indefatigable plague doctor, leads the cast, but the other players are no less rich in Camus’ character development . You may find elements of yourself portrayed in many of the protagonists in this novel, as I did, and the author does not make it a comfortable mirror to look into. Camus pulls off a culmination of close-ups of varying psychological profiles during times of extreme stress, faced with ethical moral and philosophical challenges. But seeing weakness or uncertainty in them, gave me an ability to recognise my own failings and conflicts. A confession by proxy.

“Paneloux is a man of learning, a scholar,” says Rieux to Tarrou. “He hasn’t come in contact with death, that’s why he can speak with such assurance of the truth- with a capital T. But every county priest who has heard a man gasping for breath on his death-bed, thinks as I do. He’d try to relieve human suffering before trying to point out its excellence.”

The Plague changed me. Rieux became one of the reasons I went on to study medicine. Father Paneloux contributed to my departure from religious belief. Rambert fostered a deep sense of understanding, of wishing things were back as they once were and trying everything to achieve this, but ultimately acquiescing to become part of a new reality and making the best of it. I never forgot their names, and in the coming months, perhaps, they may be looking over my shoulder, providing a moral commentary on the choices I make. I will welcome them as old friends.

PS: Camus was neither a doctor, nor was he scientific. The bacillus that causes the plague, is a disease of rats, transmitted to humans by fleas, so in fact humans do not infect each other, making self isolation and quarantine rather pointless. The plague, is more of a literary device in this novel.