By Zsanett Bahor

“We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons”

Read the first line of Doug Altman’s influential Editorial ‘The Scandal of Poor Medical Research’ in 1994, a publication, which later topped The British Medical Journal’s list of most important papers from the last twenty years. Incidentally, this statement has come to represent an incredibly important message that has persisted through time, and still rings as true today over twenty years later, as it did back then.

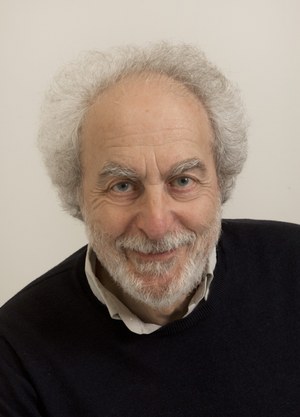

A statistician primarily, Douglas Altman made substantial contributions to a number of fields of research. He was known to the research community as a revolutionary who dedicated his life’s work to improving research conduct by working to establish better standards of practice. The simplicity and fundamentality of his arguments meant that his views on the improvement of research practice spanned multiple research domains, making a notable imprint not only on clinical research but also on pre-clinical research and systematic reviews.

He argued that sound methodology would lead to reliable scientific conclusions and that studies were highly affected by inappropriate study designs, including samples which are too small or not representative, inappropriate methods of analyses and inaccurate interpretations of results. He recognised that as much of the evidence in medical literature was intended to support medical practice, public health policy and indeed further research, its quality needed to be high. And as pre-clinical work is intended to support clinical research, this also needed to be of high quality. If studies in either research domain are not performed correctly or even not analysed or interpreted in the way they should be, then clearly they would misinform subsequent scientific and medical endeavours as well as waste large amounts of money. For many people, this is perhaps, a concept not so ludicrous. However, what he alongside many of his colleagues showed over the years is that a large proportion of the research literature suffers from issues of methodological errors, selective reporting and sometimes wrongful conclusions.

Importantly, he was also an advocate for better initial design and more complete subsequent reporting and interpretation of study results. He highlighted in his lectures that publications could be misleading if methods weren’t described completely, and if findings were misinterpreted or published selectively. He was a critical, but concurrently fearless leader in calls for transparency in research, arguing that bad research, particularly due to the misuse of statistics, could waste animals and ultimately harm patients. And of course, this consequence of a critical nature is magnified in light of bad reporting where we are not able to directly ascertain, based on a publication, what has actually been done. He recognised the simple truth that without transparency there may be no clear vision of actual scientific truth. His work highlighted that in our quest for this truth we must accurately represent what it is we see in our research. For if research is not accurately represented then what is there for future and ensuing research to build on. This, in my opinion, is the most basic concept of science.

He actively sought to improve standards by playing a key role in the founding of the Centre for Statistics in Medicine, the COCHRANE Collaboration, which aimed to provide unbiased summaries of research topics, and the EQUATOR network, aimed at improving medical research and the way it was reported. He was a real catalyst in the establishment of tools for researchers to improve their research footprint and helped develop a number of reporting guidelines. These include recommendations for randomised controlled trials (CONSORT), protocols of clinical trials (SPIRIT), observational research (STROBE), systematic reviews (PRISMA), tumour marker prognostic studies (REMARK), prediction modelling studies (TRIPOD) and finally, animal studies (ARRIVE). The ARRIVE guidelines for animal studies published in 2010 have since been endorsed by a large number of funders, institutions and most importantly journals. While the change in reporting quality remains slow, efforts like these have set the scene for a new era of pre-clinical research.

Acknowledgement of Altman’s work was widespread and his achievements in research speak volumes of the clear message he was trying to deliver and the impact he had doing so. He was Professor of Statistics in Medicine at the University of Oxford, director of Centre for Statistics in Medicine, as well as director of Cancer Research UK Medical Statistics Group. He served as The BMJ’s chief statistical adviser for over two decades and was a co-convenor of the COCHRANE Collaboration’s Statistical Methods Group.

Above all, Altman clearly identified and voiced throughout his career that research as we know it continues to be in dire need of decisive change for positive improvements to be made. And that it is everyone’s responsibility involved in the research and publication process to ensure that the published literature is an accurate and fair record of research practices past and present. He was an advocate for reliable research, for good quality research and for the accurate and complete reporting of this research – a message that is imperative we continue to promote in all fields of science today.

Douglas G Altman passed away aged 69, leaving the scientific community with the legacy of practices and attitudes of research never being the same again, thanks to his work. More than deserving of his 2015 Lifetime Achievement Award by The BMJ, the key messages of his life’s work still ring of extreme importance today, a tribute that will certainly not be forgotten any time soon:

“To maximise the benefit to society, you need to not just do research, but do it well”.

Doug Altman (1948-2018), statistician, pioneer, luminary.

Zsanett Bahor recently completed her PhD within the Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences at the University of Edinburgh.

Conflicts of interest: As a systematic reviewer of pre-clinical research, I have a lot of admiration for Doug Altman and wholeheartedly agree with his work and calls for better conduct of all science, whether that be human medicine or animal studies, for better reporting of research and for an improved scientific community that allows for science to be measured by quality and not quantity or magnitude of effect.