Professor El-Omar has selected Professor Alexander Ford from the Leeds Gastroenterology Institute/Leeds Institute of Medical Research, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK to do the next #GUTBlog. Professor Ford is the senior author on this paper.

The #GUTBlog focusses on the paper “Predictors of response to low-dose amitriptyline for irritable bowel syndrome and efficacy and tolerability according to subtype: post hoc analyses from the ATLANTIS trial” which was published in paper copy in GUT in May 2025.

“Our research group has a long-standing interest in the evidence-based management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We have conducted multiple meta-analyses of the efficacy of various drugs in IBS, including tricyclic antidepressants.[1-3] These drugs, when used at low-dose, are proposed as a treatment in IBS because they can act as gut-brain neuromodulators,[4] due to their peripheral effects on gut motility and pain sensation,[5, 6] rather than their central effects on mood. A previous meta-analysis published in this journal suggested TCAs may be effective in IBS,[1] but this was based on data from multiple, relatively small, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which used historical definitions of IBS and less stringent criteria to define response to treatment, compared with RCTs of newer drugs. Between 2019 and 2022 we conducted the ATLANTIS trial, which was a definitive double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose, self-titrated amitriptyline in 463 patients with IBS who had experienced no benefit with first-line therapies in primary care.[7] The trial was funded by the Health and Technology Assessment programme of the National Institute for Health and Care Research and was rigorously conducted with broad inclusion criteria including all subtypes of IBS. People with IBS were involved in developing the dose self-titration document, used by participants during the trial, and a patient information sheet which provided a rationale for the use of low-dose amitriptyline for IBS. These are both available free for download on the ATLANTIS trial website (https://ctru.leeds.ac.uk/atlantis/). This trial demonstrated the effectiveness of amitriptyline for IBS in primary care, compared with placebo, across multiple stringent symptom endpoints.

The size of the ATLANTIS trial meant that we were in a unique position to examine predictors of response to amitriptyline and to assess its efficacy and tolerability according to predominant bowel habit.[8] There has never been an individual patient data meta-analysis of RCTs of TCAs for IBS examining response according to patient characteristics, and most individual trials have been too small to examine these issues. Thus, predictors of response to TCAs, such as amitriptyline, for IBS have been unclear. Some clinicians have been concerned that, due to their effects on gastrointestinal motility, TCAs may have deleterious effects on symptoms for some patients, such as exacerbating constipation in those with IBS with constipation (IBS-C), mixed bowel habits (IBS-M), or unclassified (IBS-U). Indeed, some of the interpretation of the ATLANTIS trial by others focused on amitriptyline being a potential treatment only for patients with IBS with diarrhoea (IBS-D) (https://gi.org/journals-publications/ebgi/schoenfeld_dec2023/), even though the trial recruited patients with IBS of all subtypes (Figure 1).

Our hypothesis was that there would be consistent predictors of response to amitriptyline and that, because of the low doses used in ATLANTIS, the drug could have a beneficial effect on individual gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS, and would be well-tolerated, irrespective of IBS subtype. We, therefore, performed post hoc exploratory analyses to assess the effectiveness of low-dose amitriptyline, compared with placebo, according to patient characteristics and to investigate consistency of treatment effects across subgroups of clinical importance. We also assessed the effect on individual symptoms, and the safety profile, of amitriptyline by IBS subtype.

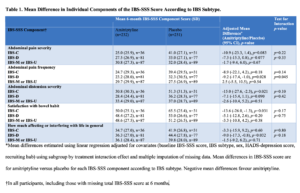

In addition, stronger treatment effects occurred consistently in men, those with higher baseline Patient Health Questionnaire-12 scores, which is a measure of IBS-associated somatic symptom-reporting, and those with IBS-D across all endpoints studied (Figures 2 to 4). There was no evidence of a consistent effect of amitriptyline according to baseline anxiety or depression scores, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, suggesting that if low-dose amitriptyline has any effects of on mood, these do not influence its effectiveness. The mean difference in individual components of the IBS severity scoring system (IBS-SSS), including abdominal pain, abdominal distension, satisfaction with bowel habit, and how much IBS was affecting or interfering with life in general, favoured amitriptyline across almost all IBS subtypes (Table 1).

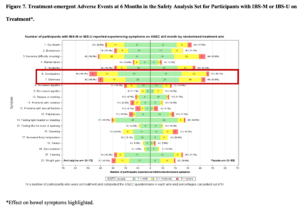

The excess adverse event rates observed with amitriptyline were similar across all IBS subtypes (Figures 5 to 7). Interestingly, however, rates of constipation were similar with amitriptyline and placebo in IBS-C and IBS-M or IBS-U, but were higher with amitriptyline in IBS-D, whereas rates of diarrhoea were similar with amitriptyline and placebo in IBS-C and IBS-M or IBS-U, but were higher with placebo in IBS-D (Figures 5 to 7).

REFERENCES

2 Ford AC, Talley NJ, Spiegel BMR, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller L, Quigley EMM, et al. Effect of fibre, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:1388-92.

3 Ford AC, Brandt LJ, Young C, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of 5-HT 3 antagonists and 5-HT 4 agonists in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1831-43.

4 Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Tornblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders of gut-brain interaction): A Rome Foundation working team report. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1140-71.e1.

5 Gorard DA, Libby GW, Farthing MJ. Effect of a tricyclic antidepressant on small intestinal motility in health and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:86-95.

6 Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology 2005;96:399-409.

7 Ford AC, Wright-Hughes A, Alderson SL, Ow PL, Ridd MJ, Foy R, et al. Amitriptyline at low-dose and titrated for irritable bowel syndrome as second-line treatment in primary care (ATLANTIS): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023;402:1773-85.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the 463 participants, and the 55 general practices involved in the study, as well as the Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee for their support throughout the ATLANTIS trial.

ETHICS COMMITTEE APPROVAL

The final protocol and subsequent amendments were approved by Yorkshire and the Humber (Sheffield) Research Ethics Committee (19/YH/0150).

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

The study was funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme (grant reference: 16/162/01). The funder had no role in data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit for publication. The ATLANTIS trial is independent research in response to a commissioned call funded by the NIHR. The views expressed in this Gut blog are those of the authors, not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Professor Alex Ford @alex_ford12399