Professor El-Omar has selected Professor Gregory A Coté, from the Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA to do the next #GUTBlog. Professor Coté is the first author on this paper.

The #GUTBlog focusses on the paper “Sphincterotomy for biliary sphincter of Oddi disorder and idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis: the RESPOnD longitudinal cohort” which was published in paper copy in GUT in January 2025.

Professor Coté writes:

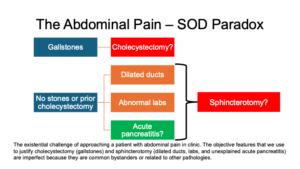

“Abdominal pain is integral to many Disorders of Gut Brain Interaction (DGBI) and a common presenting complaint in ambulatory clinics.1 Gallbladder and Sphincter of Oddi Disorders (SOD) comprise a very discrete subgroup of DGBIs that even includes idiopathic acute pancreatitis (i.e., pancreatic SOD). Few diseases in gastroenterology incite more discordant and fervent opinions, even pertaining to their existence. Their construct derives from a notoriously nonspecific symptom (abdominal pain) and use of imprecise, physician-defined characteristics to distinguish them: dilated pancreatobiliary ducts and elevated labs. Even acute pancreatitis, the hallmark of pancreatic SOD, is an inflammatory syndrome with a presentation spectrum that is broad and often instigated by overlapping triggers. Although not included in the DGBI spectrum, abdominal pain with a finding of gallbladder stones does not always mean that cholecystectomy represents a cure.2 This is the abdominal pain – SOD paradox: objective findings may not explain abdominal pain (see Figure below) yet often prompt recommendations for cholecystectomy or sphincterotomy. Gallstones, dilated ducts, and abnormal pancreatic and liver labs are more common, and thus less specific, than ever due to the aging population, greater metabolic risk, confounding medications such as statins and opioids, and better duct imaging with endoscopic ultrasound and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Detection bias could be rampant, sending a patient down the path of cholecystectomy or sphincterotomy (or both). Whether you believe in SOD or not, post-cholecystectomy ERCP is more common than ever for non-malignant biliary disease.3

The Evaluating Predictors and Interventions in Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction (EPISOD) trial4 remains iconoclastic for two reasons: first, it demonstrated that patients did not benefit from sphincterotomy for abdominal pain and suspected SOD (as per their enrolling physician, who were all renown experts) but no significant lab or duct abnormalities; second, and perhaps as important, EPISOD demonstrated a profound and sustained impact of the placebo response to a sham intervention (sham sphincterotomy). In fact, most EPISOD subjects improved during the trial, and those randomized to sham sphincterotomy did the best.

Many interpreted EPISOD as proof that SOD does not exist. However, a nihilist view towards Oddi cannot account for many plausible examples that implicate it as a cause for pain and acute pancreatitis. Gallstones causes acute pancreatitis through transient obstruction of the sphincter of Oddi. Eluxadoline, a m-opioid receptor agonist, causes acute pancreatitis and biliary SOD-like attacks, especially in those without a gallbladder serving as a protective reservoir.5 ERCP causes acute pancreatitis most when cannulation is difficult, and the sphincter complex is traumatized. These are all strong illustrations that transient pressure changes within Oddi and upstream ducts trigger pain and inflammation.

As a cure for unexplained acute pancreatitis, sphincterotomy performed poorly. Within 12 months of ERCP, 31% of patients developed a recurrent episode. This is close to observed rates among recidivists with alcohol-associated pancreatitis. This suggests that other covariates such as genetic predisposition, metabolic risk, smoking, and surreptitious alcohol were not sufficiently addressed, or that sphincterotomy cannot ameliorate acute recurrent pancreatitis once the syndrome is underway. A deeper phenotypic and genotypic analysis in acute recurrent pancreatitis will be needed. In the meantime, offering a sphincterotomy purely to ameliorate acute pancreatitis is not supported by the latest evidence.

Can a placebo response explain the findings in RESPOnD? This cannot be answered conclusively without another sham-controlled trial. However, response rates approaching 70% in specific subgroups seem too high to give up on sphincterotomy. The physician’s interpretation of the patient’s abdominal pain and traditional indicators of SOD are inadequate arbiters in the “go” or “no go” decision to try sphincterotomy. Our patients deserve better: RESPOnD clearly illustrates the need for blood, bile, or imaging biomarkers to distinguish pain originating from pancreatobiliary pressure versus countless alternatives.”

References:

- Lakhoo K, Almario CV, Khalil C, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Abdominal Pain in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1864-1872 e5.

- Comes DJ, Wennmacker SZ, Latenstein CSS, et al. Restrictive Strategy vs Usual Care for Cholecystectomy in Patients With Abdominal Pain and Gallstones: 5-Year Follow-Up of the SECURE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2024;159:1235-1243.

- Thiruvengadam NR, Saumoy M, Schaubel DE, et al. Rise in First-Time ERCP for Benign Indications >1 Year After Cholecystectomy Is Associated With Worse Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024;22:1618-1627 e4.

- Cotton PB, Durkalski V, Romagnuolo J, et al. Effect of endoscopic sphincterotomy for suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction on pain-related disability following cholecystectomy: the EPISOD randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311:2101-9.

- Harinstein L, Wu E, Brinker A. Postmarketing cases of eluxadoline-associated pancreatitis in patients with or without a gallbladder. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:809-815.

- Cote GA, Elmunzer BJ, Nitchie H, et al. Sphincterotomy for biliary sphincter of Oddi disorder and idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis: the RESPOnD longitudinal cohort. Gut 2024.

Social Media