Professor El-Omar has selected Professor Reena Sidhu to do the next #GUTBlog. Professor Sidhu is a Consultant Endoscopist at the Academic Department of Gastroenterology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, UK.

The #GUTBlog focusses on the paper “British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy” which was published in paper copy in GUT in February 2024.

Professor Reena Sidhu is the first author on these guidelines. She writes:

“We do over 2.5 million gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures annually in the UK and both the volume and complexity are increasing. Patient expectations have altered over time and rightly so.

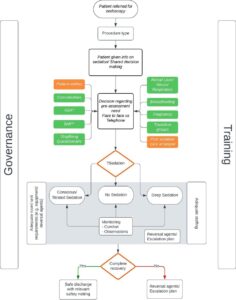

The Sedation Guidelines cover the patient journey from booking of the procedure to the pre-assessment, roles and competencies required for clinicians to deliver safe sedation, what monitoring you need and how to minimise adverse events-Figure 1 [1]. Patients should have a clear understanding of what to expect from the procedure they have consented for and the sensory experience. It is when there is a mismatch between expectation and outcome that negatively impact the patients experience.

The pre-assessment is key to balance the indication and intended aim of the procedure against the physical status (e.g., American Society of Anaesthesiologists/ (ASA class) of the patient. It is well documented that patients with a higher ASA class are at increased risk of complications during endoscopy [2]. In patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and/or a high body mass index (BMI=35 kg/m2) we recommend not only a formal pre-assessment but also enhanced periprocedural monitoring, as these patients may be at an increased risk of apnoea particularly the undiagnosed OSA [3]

We all carry out emergency endoscopy especially during GI bleed on calls. In the critically ill requiring emergency endoscopy, we recommend a discussion is had with the anaesthetic team about the choice of sedation technique and a decision about the ceiling of care with a clear plan on where the patient should be managed post procedure. Similarly, those with chronic liver disease and hepatic encephalopathy should also have proper airway support to reduce the risk of aspiration [4].

Cardiopulmonary adverse events are the most common type of endoscopy-related events, accounting for over 60% of unplanned events during sedated upper GI endoscopy [5]. These include significant cardiovascular events, such as dysrhythmias, angina, myocardial infarction or stroke especially in those who have pre-existing disease. We suggest patients at high risk of cardiac dysrhythmias undergo electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring and have supplemental oxygen during endoscopy with sedation.

The Sedation guidelines also cover specific procedures which are noteworthy. The provision of deep sedation lists across the four nations is widely varied. We suggest that complex endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and combined EUS+ERCP procedures are performed with deep sedation or general anaesthesia. This would be similar for complex lower GI procedures too.

Patients with chronic progressive neuromyopathic disorders and severely impaired respiratory function (forced vital capacity <50% predicted) often need endoscopy including for placement of percutaneous feeding tubes. We recommend adjunctive non-invasive ventilation and high-flow oxygen in these patients. For units that do not have such a provision, we hope these guidelines would form the basis of a business case.

Peri-procedural monitoring during endoscopy is well established. However, capnography has been shown to reduce the incidence of hypoxaemia and oxygen desaturations compared with standard pulse oximetry alone. Whilst the evidence stems mainly from use in the emergency setting and from dental procedures under sedation [6], for prolonged procedures and high-risk groups we would recommend this additional monitoring tool. No doubt additional infrastructure and training of personnel will be required for this.

Finally, there should be governance oversight of the process of sedation for every trust. The sedation committee acts as a chain linking national bodies that set standards to the delivery of sedation and training locally. This new guidance also recommends that at least one member in each endoscopy room must be trained in immediate life support (ILS).

The guideline will have implications for service providers, but it will help ensure safe and better sedation for our patients.

References

2.Enestvedt BK, Eisen GM, Holub J, et al. Is the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification useful in risk stratification for endoscopic procedures? Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:464–71.

3.Andrade CM, Patel B, Vellanki M, et al. Safety of gastrointestinal endoscopy with conscious sedation in obstructive sleep apnea. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017;9:552

4.Edelson J, Suarez AL, Zhang J, et al. Sedation during endoscopy in patients with cirrhosis: safety and predictors of adverse events. Dig Dis Sci 2020;65:1258–65.

5.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, et al. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76:707–18.

6. Parker W, Estrich CG, Abt E, et al. Benefits and harms of capnography during procedures involving moderate sedation: a rapid review and meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149:38–50.

7.Mitchell J, Jones W, Winkley E, et al. Guideline on anaesthesia and sedation in breastfeeding women 2020: guideline from the Association of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia 2020;75:1482–93.

Social Media

@drreenasidhu1

@Nendoscopy

@FarhadPeerally2

@drmanuknayar

@GastronauIan