Janet Mallory @malloryjem, Liz Smith @littlenurseliz & Sarah Mead Regan.

Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children (GOSH)

In March 2020, The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic. 2020 was also declared the Year of the Nurse and Midwife by WHO but has been extended into 2021 to highlight the work and challenging conditions, and to advocate investment in the nursing and midwifery workforce.

At GOSH there was a call for volunteers for deployment to North London Hospitals supporting adult Intensive care units as their bed capacity spiralled out of control with the COVID-19 patients. The three of us were redeployed in April 2020 and Christmas 2020 as part of the 126 staff GOSH sent to other hospitals. We wanted to try and describe the far reaching and memorable experiences and the steep learning curve on which we found ourselves.

We are specialists in fetal cardiology, advanced nursing practice and heart transplant. At the risk of the three of us sounding like elderly statesmen, our nursing experience added up to over 100 years with 50 of those spent in paediatric cardiac intensive care but we needed to adapt our nursing skills, practice and resilience to face the unprecedented challenges in front of us.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) code of conduct for accountability and delegation, NHS England, NHS improvement with Health Education England and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) all provided a framework and guidance on which to base the care we planned to provide.

This account details our own personal experiences and recollections but we acknowledge that these events can bring back painful memories for health care professionals.

The texts asking us to respond came through on Boxing Day – amid the tsunami of the second spike of the pandemic. New Year’s Eve passed in a blur of drug changing, rolling patients, and rapidly responding to the clinical needs of a new complex, clinical condition. Each shift began with feeling trepidation, waiting to see which intensive care (ITU) area we would be allocated to. This is in the context of new non ITU areas that would open every few days to try and accommodate the ever-rising tide of new patients being admitted requiring intensive care support

Each shift was punctuated by the continual wailing of ambulance sirens pulling up to the hospital and as nurses we wondered ‘where would these patients go?’ and ‘who would care for them?’ These patients would be nursed in areas that weren’t set up for this level of complexity with challenges such as a scarcity of plug points, equipment, cramped quarters and noise which was a constant battery on your senses, to the point of overload.

Physical symptoms of anxiety were a common occurrence for us especially leading up to a night shift – heart palpitations & loss of appetite. We had to prepare for the logistics of travel, orientation to new environments and leaving much loved families who were feeling the strain and worry like the rest of the population. Were we putting them at extra risk?

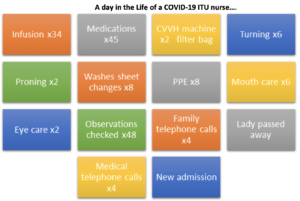

However, once at work there was no time to feel anything other than the unrelenting rhythm of the shift. The demands of donning and doffing and keeping up with the overwhelming needs of our patients was married with the familiar comfort of paper charts and coloured pens! Personal hydration was a challenge due to the complicated and lengthy process of donning and doffing and the complexity of taking breaks, knowing you would take the precious commodity of time from another colleague and away from patient care to leave the clinical area.

The multi-disciplinary team of helpers was an invaluable force, including fainting medical students (revived with a Capri-Sun) and combat army medical technicians with a strong gag reflex! We had physiotherapists, psychologists, research nurses, clinical nurse specialists, ward nurses, administrative staff and consultants – the human aspect of people underneath the personal protective equipment (PPE).

Often, as the only trained nurse we were required to give all intravenous medication, titrate infusions to clinical need and be attentive to the constant renewal of infusions and the strict regime of national Covid-19 medication trials. As patient stays extended, their care progressed but the difficulties of caring for more than one patient at a time with delirium and a tracheostomy put extra demands on a stretched nursing service.

We couldn’t have managed this without resilience but how is this measured? The teams suffered moral distress, at times unable to fulfil the compassionate role for which we had trained leading to feelings of professional grief. Helping relieve pain and suffering is rewarding but we were faced with feeling powerless when limits of care were reached and the overstretching of resources was felt.

The high numbers and acuity of patients could mean an ITU nursing ratio 1:4, and doubling to 1:8 at breaks. The daily impact of talking to relatives on the phone, FaceTiming their loved ones and the daily exposure to death, some who we met briefly and others were part of our long term care. Seeing their shoes and personal belongings such as a book under the bed, could hit us hard. The real-life stories behind the lines of prone patients. What happened to them and what was their story? We were not on the regular email updates so relied on anecdotal information and brief handovers.

This experience for us came without a textbook as we reflected on our own mortality with loss of staff, family, friends and patients. We used our professional background and personal resilience to provide nursing care to the best of our abilities, supporting adult intensive care in the framework and uncertainty of a national pandemic. Research is ongoing into the future effects of redeployment on health care staff in the UK. Our Trust offered Trauma Risk Management (TRIM) and a plethora of wellbeing & support, however we found that as we discussed and wrote about this experience together, it proved to be a natural and invaluable period for debrief and reflection.