Last week, I learnt with great sadness of the death of Eileen Baxter, who died in an Edinburgh hospital in August. Mrs Baxter’s cause of death was multiple organ failure. Sacrocolpopexy mesh repair is named as an underlying cause on her death certificate, meaning the mesh triggered the chain of events leading to her death.

Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s First Minister, responding to a question raised in the Scottish Parliament said: “the use of mesh, other than in exceptional circumstances, remains under suspension in NHS Scotland…..”We’ve seen the number of operations fall dramatically. In the six months to March this year there were 33 operations carried out. That compares to over 1,100 in a similar period in 2013/14.”

What Mrs Sturgeon didn’t understand was that she was acknowledging in 2013/14 that at least 1000 women a year were undergoing unnecessary operations – the year Mrs Baxter had the mesh inserted – If you don’t need it now why would you need it then? You don’t stop doing surgery if the benefits outweigh the harms, do you?

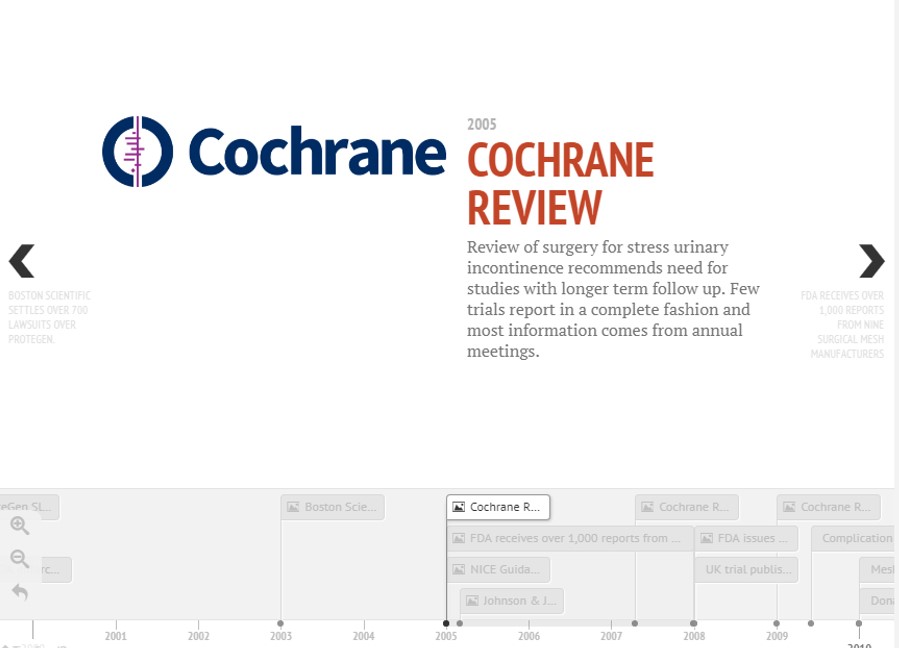

The evidence base for surgical mesh is poor – actually, it’s mostly missing – and there is a shortage of evidence about harms. I wrote about it here: it’s been 13 years since NICE stressed the need to inform women of the lack of long-term outcomes, and `Cochrane recommended the need for studies with longer term follow up.

Transvaginal Mesh Timeline – CEBM

In July 2011, the FDA released an Update on the Safety and Effectiveness of Transvaginal Placement for Pelvic Organ Prolapse and identified that serious concerns and adverse events were NOT rare, contrary to a previous 2008 FDA public health notice. Therefore, 2011 should have been the year Scotland – along with the rest of the world – took the harms of mesh seriously, began an inquiry and removed it from the market.

However, this has not been the case. The lack of evidence has meant that significant numbers of women have been harmed, some of them with devastating consequences before action has been taken. The lack of trials and the lack of a mesh implant registry has meant the accumulating evidence of harm has come too late for many.

Primum non nocere means “first, to do no harm” – it is a philosophy ingrained in medical students but seemingly lost in the real world of clinical practice. It is better to do nothing than risk causing more harm than good. This is particularly relevant for mesh, given the absence of evidence pointed out by NICE, Cochrane and the FDA, along with the degradation and infection risks with polypropylene outlined by Donald Ostergard in a 2011 review in the International Urogynaecology Journal (all of which had accumulated before the FDA decided to clear the majority of mesh products).

Year: Problem

1987: At the time of mesh insertion there is a race to the mesh surface between bacteria and your defense cells.

1991: Bacteria stick to the surfaces of the mesh and produce a film which protects them from the human immune system and antibiotics.

1993: Multifilament mesh promotes infection.

1996: Bacteria move along synthetic polymeric fibers in mesh.

1998: Polypropylene mesh shrinks 30-50% after 4 weeks.

1999: Surface roughness promotes wicking of bacteria. Ten bacterial colony forming units are sufficient to infect up to 15% of the mesh.

2000: Bacterial colonization is found in one third of surgically removed meshes .

2001: smaller pores prevent vascularisation.

2002: The extent the bacterial stick to the mesh depends on the mesh surface area. The bigger the are the more they stick. Multifilament meshes have twice the surface area compared to monofilament meshes.

Degradation, infection and heat effects on polypropylene mesh for pelvic implantation: what was known and when it was known. Ostergard DR. Int Urogynecol J. 2011 Jul;22(7):771-4. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1399-y.

Given the issues outlined you would consider the bar for approval of mesh, the evidence needed for its use and the post-marketing surveillance requirements would have all been set at a very high bar – they weren’t. The next time you offer or are offered a healthcare intervention, in the absence of evidence and where the potential to do harm is significant, then consider, first do no harm.

BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine – original evidence-based research, insights and opinion

Read more in the Welcome to BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine Editorial.

Competing interests

Carl has received expenses and fees for his media work including BBC Inside Health. He holds grant funding from the NIHR, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research, The NIHR Oxford BRC and the WHO. He has also received income from the publication of a series of toolkit books. CEBM jointly runs the EvidenceLive Conference with the BMJ and the Overdiagnosis Conference with some international partners which are based on a non-profit model. he is a clinical advisor to the UK Gov’ts All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on surgical mesh.

Full disclosure see here: