Patients and their care partners are usually the first to notice new or changing symptoms and are the connecting “thread” between different healthcare encounters. In this article Sigall Bell, Fabienne Bourgeois, Stephen Liu, and Eric Thomas—along with patient partners Betsy Lowe and Liz Salmi—describe the co-development of an online tool called “OurDX” (Our Diagnosis) to engage patients and families in the diagnostic process

Sigall Bell, associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School; Fabienne Bourgeois, assistant professor of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School; Stephen Liu, associate professor of medicine, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth; and Eric Thomas, professor of medicine, McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston on behalf of the OurDX development team*

Diagnostic error is common, costly, and distressing for patients and healthcare professionals alike.1 Breakdowns in communication can arise when consultations are time pressured or fragmented, resulting in challenges to listening, interpreting, and acting on patients’ symptoms, signs, and test results. Most clinicians want to know about process breakdowns and “near misses” that could lead to diagnostic error, but few receive this feedback, resulting in missed opportunities for improvement.2

Evidence suggests that engaging patients in the diagnostic process is critical to prevent diagnostic error.1 Over the last decade, we’ve learnt that sharing visit notes electronically with patients and families (referred to as “open notes”) helps them remember diagnostic tests and referrals, strengthen relationships with providers, and identify breakdowns in the diagnostic process.3-5 Based on this experience, we decided to develop a new tool, OurDX, to more actively co-produce the diagnostic process with patients and families.

Using data from diagnostic breakdowns to develop OurDX

We started by convening a 14-member multistakeholder group including patients and families, diagnostic error and patient engagement experts, clinicians, and healthcare delivery researchers. Participating patients and families included individuals from diverse racial backgrounds, and who had lived experience with chronic illness, complex care, or disability. The group’s work focused on establishing a patient-centred framework to understand and describe diagnostic breakdowns experienced by patients and families.6 We defined a patient-reported diagnostic process-related breakdown as a problem or delay identified by patients that mapped to any step of the diagnostic process, as outlined in the NAM conceptual model.1 Three researchers (one internal medicine doctor [SB], one paediatrician [FB], and one patient [LS]) then applied the framework to analyse—using standard qualitative methods—over 2000 patient-reported ambulatory errors in two existing datasets: a national Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) survey on the American public perception of medical errors,7 and a survey of patients using open notes at three health organisations in the United States.8

This study showed that the main patient-identified problems which can lead to diagnostic breakdowns include: 1) failure to accurately capture and record patients’ history; 2) inadequate communication, including patients not feeling heard or misalignment between patients’ and providers’ views about what’s important; 3) failure or delays related to the explanation of symptoms or next steps; and 4) test or referral breakdowns, such as missing orders for recommended tests, scheduling delays, or problems with interpretation and communication of results.6

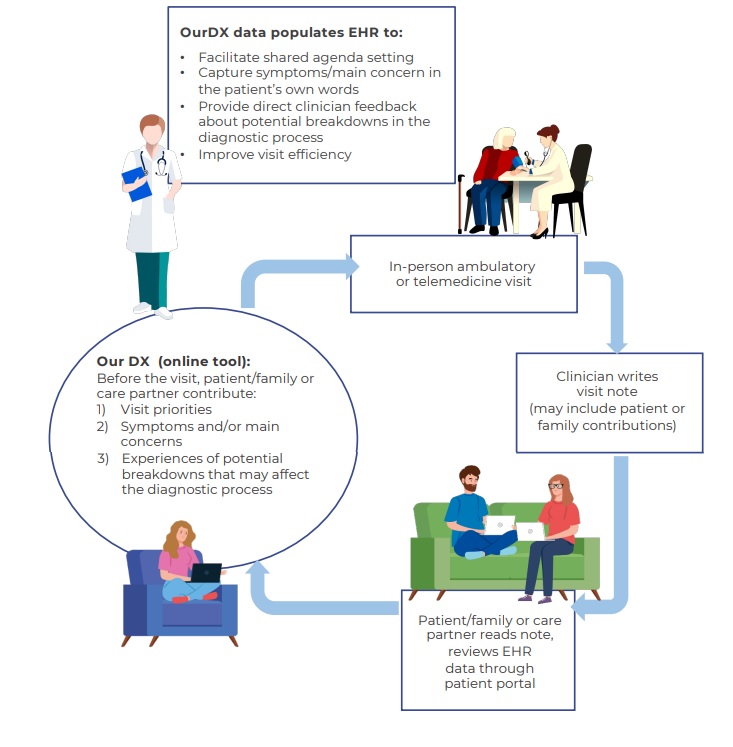

On the basis of this analysis, a workgroup—including patients and family members who receive care at several different organisations, physicians, a user-centred design expert, and representatives from the office of patient experience—began designing OurDX to help tackle these problems. OurDX builds on using the electronic health record (EHR) as a common shared vehicle for full exchange of information between patients and clinicians. In addition to encouraging patients to read notes, it provides a dedicated space in the EHR for patients to set out their priorities for the clinic visit, document their symptoms and concerns, and include any information they have about potential breakdowns related to the diagnostic process. Patients’ contributions become part of the EHR, and clinicians can include their comments in the notes they write after the consultation, potentially decreasing documentation burden. OurDX builds on “Open Notes,”9 “Our Notes”10 (which invites patient contributions to note), and IHI’s “What Matters To You,” by creating an engagement cycle before and after the visit that is focused on the diagnostic process [Fig 1].

During our planning discussions with patients and families, we learnt about the physical and emotional impacts of diagnostic error and the absence of an effective way to provide feedback to clinicians about diagnostic breakdowns in real time. Patients expressed gratitude for access to their health information and for the opportunity to help healthcare providers “get it right.” They also prioritised using a positive frame for OurDx that is relationship-centred.

Design of OurDX to reflect patient and clinician priorities

Clinicians worried that OurDX content might create additional burdens in time constrained visits. But evidence demonstrates the value of patient contributions to raise awareness about clinically relevant diagnostic breakdowns, some of which may otherwise be invisible to clinicians.4 Bearing these factors in mind, we designed questions to focus on actionable information related to the current visit. In addition to open ended items, we used checkboxes for patients to indicate if they had recent visits to an emergency department or another healthcare system for the same problem, or other factors that could help clinicians quickly flag visits that are at higher risk for a diagnostic breakdown. We designed OurDX with a collaborative spirit—inviting patients to help clinicians get it right—and included a positive feedback question to also identify things that are going well. Finally, we underscored provider feedback about workload and relevance in our assessment.

We developed educational materials and tested OurDX with members of the patient and family advisory council, seeking additional feedback from one hospital’s quality improvement group and the clinics at both hospitals where the tool was planned for implementation. We discussed the system with participating providers and described how to find patient responses to OurDX in the EHR, and how to import them into progress notes. Then we set up a system in which patients receive an invitation from the clinic to complete the OurDX tool electronically several days before their scheduled visit through the patient portal or by email. We implemented OurDX in 2021 in five clinics, including both primary care and specialty care at Boston Children’s Hospital and Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center. No new technology has been required since most standard EHRs have built-in functionality for a pre-visit survey.

Betsy Lowe, volunteer patient/family adviser with multiple chronic conditions and 11 years of experience at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA

As a mother of three children, I interact regularly with doctors, nurses, and physician assistants, and feel responsible for the health and wellbeing of our family in ways that are visible and invisible to providers. For our family, the process of reaching a diagnosis has on occasions been a complicated, confusing, and emotionally exhausting journey. But this experience is rarely discussed in clinic visits, nor is it documented in our notes—even though it becomes a core piece of who we are, how we move through the world, and how we interact with healthcare professionals. It also affects how we live with our diagnoses, our trust in our providers, and our willingness to engage in treatment. I have often wondered how and when to share these parts of our story.

My work on OurDX included participation in the development of the patient-centred framework for diagnostic breakdowns and the Our DX tool. The experience was rewarding because it gave me insight into the problems providers face on a daily basis, trying to balance the strong desire to care for patients with constrained resources and time. Imagining how I would respond to the OurDX questions before a visit for myself or my children helped me see how inviting patient and family contributions before the visit might encourage open and honest discussion about what it is like for us to go through a challenging diagnostic process. Listening to clinicians and patients on the team enabled me to understand how easily some important pieces of the patient’s story or clinical history can be unintentionally overlooked or mistaken, and how these problems can affect diagnosis or treatment.

I continue to wonder how and when patients like me can and should share more of our story and how organisations can seek systematic feedback on our experiences. Access to electronic medical records has been valuable because I have gained a better understanding of how clinicians think, and I use my record to orient myself ahead of my next visit. I believe that all healthcare organisations need to find creative ways to invite patients and families to share more about their journey, in order to improve care.

Liz Salmi, patient-researcher and person living with cancer

The first time I read my medical record was eight years after my brain cancer diagnosis. Viewing my record was eye opening: it answered my questions, reminded me of my care plan, and reinforced that my doctors were truly listening to me. After enduring two brain surgeries and two years of chemotherapy, I wish I could have seen my record sooner.

When my insurance changed, I switched doctors and requested my records. I was surprised by the $725.40 fee, which I’ve learnt was a not uncommon barrier to patient record access before the 21st Century Cures Act, which mandates patient access to their electronic records in the US.11 12 I noticed some mistakes in my chart: my age at diagnosis was listed as 19 instead of 29, and my brain cancer type was incorrect.

I’m not the only person to spot inaccuracies in my medical record. Research shows that one in five people who read their notes find errors, many of which they consider important.4 However, the process for patients to report errors is complicated, varies by organisation, or simply does not exist. A tool like OurDX could help me alert my doctor to the errors in my record. It also sends patients the message that our input is valued and welcomed.

As a patient-researcher, I participated as a patient-coder in the qualitative analysis of patient reports of medical error, informing OurDX design. The most surprising thing I discovered from reading these patient accounts is how my view of “diagnosis” changed. I used to think of diagnosis as a “thing I have”—an unchanging attribute. “She is left-handed, she has recurrent grade II astrocytoma.” I now understand diagnosis is not just a thing, but also a process.

Preliminary findings and future directions

Sigall Bell, Fabienne Bourgeois, Stephen Liu, and Eric Thomas

So far, the number of patient responses to OurDX is over 3000, which has exceeded our expectations. A few patients have declined use of OurDX due to pandemic-related survey fatigue. As anticipated, the number of patient-reported breakdowns has been relatively small,6 and we have found that giving patients the opportunity to write about their experience and views has resulted in patients sharing positive feedback as well. Some clinicians report that receiving agenda items and patient-reported histories before or at the visit helps organise the visit, engage patients, and accelerate diagnosis in some instances. For example, patient-provided descriptions of current symptoms have prompted diagnostic studies such as lab tests or imaging to be arranged before the visit, so that results are available sooner. Early concerns about time to read OurDX or pressure to address clinically unimportant concerns have not emerged as major issues, and may be offset by greater clinician efficiency in gathering information and patients who are more prepared for visits. Early data suggest OurDX may decrease documentation burden by shortening provider-generated patient histories in notes with OurDX patient contributions.

Co-developing OurDX with patients and families has helped us to learn more about how to engage patients in the ambulatory diagnostic process, which is challenging since it may involve multiple clinic visits and interactions with several different doctors. Formal evaluations of patient reports and clinician surveys are underway and we have translated the tool into Spanish. We believe OurDX can better align patient priorities with clinician agendas, ensure the patient story is captured correctly, facilitate timely completion of diagnostic tests or referrals, and help patients feel heard—underscoring their vital role in the diagnostic process.

Key messages:

- Recent advances in technology, transparency, and policy open the door to new ways of engaging with patients and families, such as co-producing and sharing visit notes.

- Patients and families have unique knowledge and experience of their symptoms and events that transpire between healthcare visits, and can help complete a 360-degree view of the diagnostic process, enabling more timely and accurate diagnoses.

- Engaging patients and families in diagnosis with tools like OurDX provides opportunities to enrich patient/family understanding of, and contributions to, the diagnostic process; deepen clinician understanding of the patient/family’s journey; and improve the quality and safety of care.

Figure 1: The OurDX patient engagement cycle before and after the visit

*OurDX development team: Sigall Bell, Fabienne Bourgeois, Michele Domey, Stephen Liu, Elizabeth Lowe, Aniqa Mian, Sandy Novack, James Ralston, Lisa Rubino, Liz Salmi, Eric Thomas

Sigall K Bell is associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of patient safety and discovery at OpenNotes, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Fabienne Bourgeois is assistant professor of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School and associate chief medical information officer at Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Stephen Liu is associate professor of medicine at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH.

Eric J Thomas is professor of medicine at the McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), and director of the UT Houston-Memorial Hermann Center for Healthcare Quality and Safety and associate dean for healthcare quality, in Houston, TX.

Elizabeth Lowe is a patient advocate and member of the patient and family advisory council at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Liz Salmi is a patient-researcher, person living with cancer, and senior strategist at OpenNotes, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Statement: The authors have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: This work was supported by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (SB, FB, SL, ET, LS). SB and FB also report funding from the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine for developing OurDX for Spanish-preferring patients.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the patients and families who participated in surveys and feedback informing this work; Amanda Norris for her design of the OurDX figure; Nicolas Hart and Brianna Mahon for their assistance in implementing OurDX; Kendall Harcourt for her assistance in project management; Jan Walker and the OurNotes team for contributions from the OurNotes effort; members of the multistakeholder advisory group that guided development of the Patient-Centered Framework, including: Feleshia Battles-Byrdsong, Cait DesRoches, Patricia McGaffigan, Lauge Sokol-Hessner, Suzanne Schrandt, Sue Sheridan, and Glenda Thomas; and additional patient advocates and patient experience contributors to the OurDX development team, including Michele Domey, Aniqa Mian, Sandy Novack, James Ralston, Lisa Rubino, and Sara Toomey.

References

[1] Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR, et al. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care; 2015. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/read/21794/chapter/1

[2] Croskerry P. The Feedback Sanction. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1232-1238. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00468.

[3] Bell SK, Folcarelli P, Fossa A, et al. Tackling Ambulatory Safety Risks Through Patient Engagement, Journal of Patient Safety: April 27, 2018 – doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000494.

[4] Bell SK, Delbanco T, Elmore JG, et al. Frequency and Types of Patient-Reported Errors in Electronic Health Record Ambulatory Care Notes. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e205867-e205867. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5867

[5] Blease CR and Bell SK. Patients as diagnostic collaborators: sharing visit notes to promote accuracy and safety. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019 Aug 27;6(3):213-221. doi: 10.1515/dx-2018-0106.

[6] Bell SK, Bourgeois F, DesRoches C, et al. Filling a Gap in Safety Metrics: Development of a Patient-Centered Framework to Identify and Categorize Patient-Reported Breakdowns related to the Diagnostic Process in Ambulatory Care. BMJ Qual Saf in press.

[7] Americans’ experiences with medical errors and views on patient safety. Final report. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/about/news/Documents/IHI_NPSF_NORC_Patient_Safety_Survey_2017_Final_Report.pdf

[8] Walker J, Leveille S, Bell SK, et al. OpenNotes After 7 Years: Patient experiences with ongoing access to their clinicians’ outpatient visit notes. J Med Internet Res 2019;21(5):e13876

[9] Delbanco T, Walker J, Bell SK, et al . Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: A quasi-experimental study and a look ahead. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:461-470

[10] Mafi JN, Gerard M, Chimowitz H,et al. Patients Contributing to Their Doctors’ Notes: Insights From Expert Interviews. Ann Intern Med 2017; DOI: 10.7326/M17-0583

[11] Salmi L, Blease CL, Hagglund M, et al. US Policy requires immediate release of records to patients. BMJ 2021;372:n426

[12] Lye CT, Forman HP, Gao R, et al. Assessment of US Hospital Compliance With Regulations for Patients’ Requests for Medical Records. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1(6):e183014. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3014