Rocking the boat and staying in it: how to succeed as a radical in healthcare

Rocking the boat and staying in it: how to succeed as a radical in healthcare

Part 2: Start by improving myself

Helen Bevan blogs about topics related to improvement, innovation and change on a big scale. Helen works as part of the Delivery Team of NHS Improving Quality, @NHSIQ, the national improvement team for the NHS in England. All views are her own. Follow her on Twitter @HelenBevan.

Yesterday, I was clever so I wanted to change the world.

Today, I am wise so I am changing myself

Anon via Twitter

A lot of people responded to my last blog which was an introduction to tactics for thriving and surviving as a healthcare radical. Four things struck me about that response:

- There are a lot of radicals/rebels out there in the healthcare system; passionate people who support the patient-centred goals of healthcare organisations, who are willing to take responsibility for change but who question and challenge the current ways of going about change

- “Radical” status isn’t related to hierarchy or position and we don’t have to work in the NHS to qualify as a healthcare radical. A wide variety of people responded to the blog; this included radical patient leaders and radical Chief Executives

- We have to find ways to unite and mobilise this radical community; this is a latent and potentially powerful reservoir of energy for change

- We must help healthcare leaders to understand the difference between a radical/rebel and a troublemaker (or good rebel/bad rebel) and exploit the talents of that radical/rebel community for the greater good

As I trailed in the last blog, I’m going to discuss four of the key tactics for healthcare radicals in more depth over the next few weeks. The first of these tactics is start by improving myself.

As a change agent, I frequently look at the world around me and identify things that need improving. If we are to deliver safe, high quality care to every patient and to make the most of our precious healthcare resources, we need to continuously improve processes and systems of care. Yes, this is really important, but as healthcare radicals we have to start at an earlier point in the foodchain of improvement. To quote Aldous Huxley: “There’s only one corner of the universe you can be certain of improving, and that’s your own self.” So before I am tempted to launch into a massive effort to influence other people change the way they think or do things, I have to start by reflecting on and changing myself. I have to understand myself, because the person who will be the hardest for me to lead through change is me. I’m always inspired by the work of David Whyte who is a corporate poet. He understands this completely when he says: “I do not think you can really deal with change without a person asking real questions about who they are and how they belong in the world.’ (The Heart Aroused 1994)

I am writing this blog in the week after the publication of Don Berwick’s recommendations to improve the safety of patients in England: “A promise to learn – a commitment to act” so I thought I might use the Berwick report to illustrate some of the points I want to make about healthcare radicals. Like so many leaders of improvement in the English National Health Service, I am thrilled to see these recommendations, which are a compelling call to action for change, based on evidence, to make the English NHS the safest system for patients in the world. As Paul Batalden said in a response to the earlier report of the Francis inquiry, healthcare is at the same time a “simple, complicated and complex” phenomenon. Some of the commentators who have criticised the Berwick report wanted to see more “hard edged” recommendations related to mechanisms for enforcement or regulation, checklists, minimum standards and/or behavioural incentive systems. My response is that many of the solutions that these commentators seek are “simple” solutions which are not, on their own, reliable levers for change in a highly complex world. Experience shows us how these simple solutions can push the system in a certain direction, distort priorities and often (unintentionally) create the opposite effect to the changes we are seeking. The gift of the Berwick recommendations is that they offer us a starting point for an aligned set of actions, at multiple levels of the system simultaneously, that give us (collectively) a fighting chance to transform patient care. As a longtime student of large scale change, I would say that the Berwick recommendations offer a more sophisticated and well-constructed blueprint for change in a complex system than we have seen in any previous change plan for the NHS.

So where do we, as healthcare radicals, fit in this complex system of change? It would be easy to look at the recommendations of the Berwick report and question whether we, as individual change agents, can make a contribution, at least in the short term, whilst our leaders work out how they are going to respond to the recommendations. After all, the Berwick report says that safety is mostly NOT about individuals; it is the systems, procedures, conditions and environments that cause the most patient harm. Consequently, many of the recommendations are for “systematic” solutions, involving setting up systems for continuous learning, innovation and improvement. There is a risk that we radicals might feel that we have to take a back seat whilst our organisations and leaders take responsibility for establishing these new systems, waiting for the patient safety change agenda to get around to including us, so we can play our part.

But we just can’t just wait whilst someone else starts the change as a) it might be a long wait and b) more patients are likely to be harmed in the waiting period. I’m not saying that we should rush off and start making changes on our own, regardless of what is being planned in the wider system. However, as healthcare radicals, we do need to be creating our own goals for change right now, strategising about how and where we can best make our contribution to the bigger purpose, reaching out and building alliances with others and demonstrating willingness to move the change agenda forward, despite the challenges and scepticism that might face us. When we have the courage to act proactively like this, we find that most organisations will value these behaviours, even where the organisation doesn’t currently have a strong improvement or learning culture. You see, each of us who leads and/or facilitates change is a signal generator. Our words and deeds are constantly scrutinised and interpreted by the people around us in our teams, organisations and in the wider system. The amplification effect of what we do and say is far greater than we imagine. The most powerful way to inspire others to change is to be the vanguard for that change. If we want other people to take a risk and change the way they think or organise for patient safety, we have to take the lead. I like the way that Tanveer Naseer describes it:

You have to be the first one up and off the high dive you’re asking others to leap from. Ask yourself: where am I playing it too safe and what is that safety costing me? Then leap from your platform of safety into the cold water of change.

One of the aspects of the Berwick report that I most welcome (and fits with the evidence base on large scale change) is the focus on learning as a strategy for transformation. The report sets the bold goal of transforming the NHS into a learning organisation that continuously reduces patient harm through learning. I want to link this learning theme with another key theme in the report: driving out fear. The report stresses the toxic effect of fear on both safety and improvement. I would add that fear is also the biggest barrier to learning. It’s hard to learn when you feel fear. The Berwick proposals require many organisational leaders (and even people who perceive themselves as healthcare radicals) to move away from a status quo that they feel comfortable with into a brave new world of quality control, quality improvement and quality planning on a scale never seen before and that can be a scary thing. As Peter Senge wrote in The Fifth Discipline (as quoted by Chip Bell):

“When we see that to learn we must be willing to look foolish, to let another teach us, learning doesn’t always look so good anymore…Only with the support and fellowship of another can we face the dangers of learning meaningful things.”

The evidence base on learning organisations emphasises the importance of leaders who role model humility and vulnerability. So we have to ensure that the coaches, teachers and mentors that deliver and support this learning have to be able to recognise the fear and create positive learning experiences, focused not just on safety science and quality improvement methods but on the emotional processes of change. To quote Rosabeth Moss Kantor, “Leaders are more powerful role models when they learn than when they teach”.

This situation creates a specific call to action to healthcare radicals. We, the signal generators at the vanguard of change, must embrace the spirit of the student. This means taking responsibility for our own learning and being open to continuous learning; embracing new ideas and approaches and being willing to challenge and change our existing belief systems. We have to be the best, most active, most humble learners.

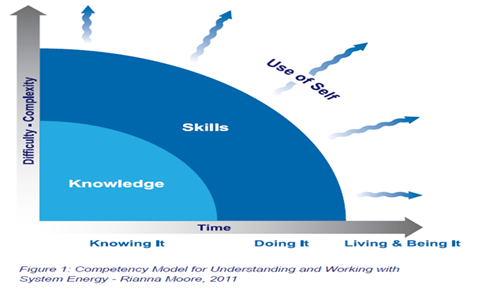

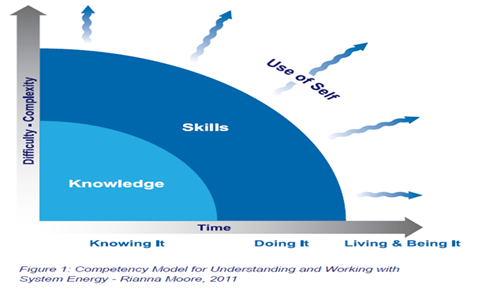

In addition, our learning must move beyond knowledge and skills. For healthcare radicals it is important, but not enough, to continuously build our knowledge of improvement methods and approaches. It’s also important, but not enough, to take responsibility for our own development as skilled leaders or facilitators of change. What sets healthcare radicals apart is the extent to which we purposefully seek to live and be improvement, in the way we operate in the world and in our interactions and relationships with others. I think that the diagramme below from Rianna Moore sums this up very well. It’s only when we live the things we believe in (that is, when

we can align our sense of deeper life mission or calling, our values and the activities that we undertake every day) that we can truly energise our teams and organisations by working from our true selves and make our full contribution as healthcare radicals.

Being a great change agent is about knowing, doing, living and

being improvement

The Berwick recommendations provide us with a one of the best opportunities ever for radical system change. However, history tells us that organisational or system transformation is always preceded by personal transformation. So if, as organisational radicals, we want to play our role in this transformation, we have to focus deeply on our own perspective and the ways we interact with and influence others. The more people we can

influence in a positive way and the more that we (as organisa

tional radicals) can unleash that powerful reservoir of energy for change, the mo

re our influence and impact will grow.

Individually and collectively, we can play a truly significant role in helping to implement the changes that are needed in healthcare processes and systems; delivering the outcomes and experiences that our patients deserve and building the continuous learning and improvement system that will make the English NHS the safest healthcare system in the world.

Calls to action for this week

- Read A promise to learn – a commitment to act from the perspective of a healthcare radical; consider what your input will be to making the potential a reality and how you can contribute to the wider goals of your organisation, system or community for patient safety

- Think about how you adopt or build the spirit of the student and how your role as an active learner can be a catalyst for others and for the “learning organisation” movement

- Reflect on the extent to which you are knowing, doing, living and being healthcare improvement and patient safety; to what extent are you operating from your true self? How can you make your impact as a healthcare radical even more effective?

|

I declare that that I have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and I have no relevant interests to declare.