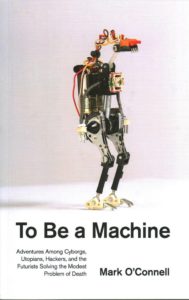

To Be a Machine: Adventures Among Cyborgs, Utopians, Hackers, and the Futurists Solving the Modest Problem of Death by Mark O’Connell, London: Granta, 2017, 244 pages, £12.99.

Reviewed by Anna McFarlane, University of Glasgow

Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine documents the writer’s encounters with a series of self-proclaimed ‘transhumanists’; those who subscribe to the belief that life can be extended and broach the possibility that death itself might be eradicated in the coming years thanks to the exponential rise of technology. It is an intriguingly contradictory belief system, one that finds humanity lacking in its current form and wishes to transcend that state in a kind of eschatological rapture; but one that invests humans with the power to overcome the very conditions of their limitations through scientific progress and discovery. O’Connell’s interviewees are almost exclusively American, by choice if not by upbringing, and tend to make their homes around the technological hubs of Silicon Valley, a sunny, laid-back environment where this kind of techno-utopianism is something to be believed in.

O’Connell’s time with these characters brings him from cryogenic facilities, to those working with diabetes medications to find the means of medical life extension. Whereas the field of the medical humanities tends to look for ways to humanise the technical process of doctoring in an increasingly technical environment, these are people who are willing to give up their agency into the non-human hands of medical technology in exchange for the promise of eternal life. Many of these characters are brought to their belief in transhumanism through close encounters with the frailty of their bodies. For example, Natasha Vita-More, chair of an organization called Human Plus, realized her calling to transhumanism after an ectopic pregnancy meant the loss of her unborn child. O’Connell writes that, ‘when she talked now of her path to transhumanism, this was the time of her life she continually returned to, the moment when she realized, on a visceral level, that the human body was a feeble and treacherous mechanism, that we were each of us trapped, bleeding, marked for death’ (39). For those who implicitly put their trust in positivism, or at least in the neutrality of scientific progress, such moments of frail human identification with the flesh can turn disease, and even death, into an instrumental problem to be solved. One of O’Connell’s interviewees, a biomedical gerontologist named Aubrey de Grey, holds ‘that aging was a disease, and furthermore a curable one, and that it should be approached as such: that we should be prosecuting a great counteroffensive against our common enemy, mortality itself’ (180). Conceptions of age and death as enemies that must be fought with the use of all our scientific prowess extend the field of what can be considered a ‘medical’ issue, to encompass much of speculative science more broadly. In the thinking of transhumanism, medicine has less to do with humanism than with a superhuman wielding of the latest technology.

While some seek to solve the problem of death, others put technology to the opposite use. The (very human) desire to escape the fear of death and bodily vulnerability comes together under the rubric of transhumanism with capitalist and militaristic imperatives to create technologies that are by design protected from the threats that arise for human combatants in the field. O’Connell attends a robot expo, the Robotics Challenge organised by the US’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). O’Connell finds himself charmed by the anthropomorphic pratfalls of the robots as they attempt tasks that would be utterly straightforward to human protagonists – getting out of jeeps, climbing stairs, or walking over rubble – but notes the sinister subtext to such an event, which has at its heart the desire to create invulnerable beings that would further cement the USA’s global military dominance. This concern about the power behind new technologies extends to the medical field of life extension. O’Connell does ask about the fairness of a life extension technology that would inevitably find itself solely in the hands of the wealthy, maybe even just the super-rich, but is met with some assertions about the trickle-down effect that such technologies might have were they to become popular and affordable. The transhumanists seem to give little consideration to the possible population problems that might result from the unequal availability of life extension technologies and the societies that might be inadvertently engineered through such interventions. For that we have to look to science fiction, like 2015’s Elysium.

This is O’Connell’s first full-length book for a general readership, following his PhD and the resultant monograph on John Banville’s fiction, and his writing at times bears the signs of that academic bent as his observations are given depth through references to Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, and some insightful thoughts on the importance of science fiction in shaping this particular brand of utopianism. Where the writing has not quite found its feet is perhaps in its juggling of interviewees – sometimes there are too many eccentric characters introduced in a short space of time and the reader feels like a stranger at a party, trying to memorise names and find a foothold in the conversation. However, when O’Connell finds a subject he can stick with for longer periods his writing is warm and humourous, and he is unafraid of bringing his personal experiences into the text, finding his attachment to an embodied and mammalian existence in his love for his infant son, and the fear of death he experiences when he finds himself in hospital for a biopsy. In the future, he may well develop into a writer with the popular humour of Jon Ronson coupled with a self-aware philosophical relationship with his material.