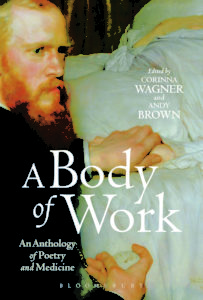

Corinna Wagner and Andy Brown (Eds.) A Body of Work. An Anthology of Poetry and Medicine. London, Bloomsbury, 2016, 532 pages

Jack Coulehan, MD, Center for Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care, and Bioethics, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794 USA

At first glance medicine and poetry seem like strange bedfellows. Yet, consider the fact that medicine has strong roots in the world of art and symbols, and poetry can often be, as the editors of A Body of Work put it, “the deep music of bodies in pain.” Because of its brevity and immediacy, poetry occupies a special place in the medical humanities movement, which seeks to explore issues of illness, suffering, and healing through the lenses of literature, history, philosophy, cultural studies, visual arts, and other humanities. In their introduction to A Body of Work, editors Corinna Wagner and Andy Brown ask rhetorically, “Poetry: What Is It Good For?” This brings to mind the famous lines from William Carlos Williams’ late poem “To a greeny asphodel,” “It is difficult to get the news from poems, / yet men die every day / for want of what is found there.”1 Perhaps poetry is like a vitamin, required for human flourishing, if not survival.

Several anthologies of poems about illness, disability, medicine, and healing have appeared in recent years. In addition, anthologies of poems written by doctors, nurses, and other clinicians are available. Does A Body of Work contribute anything substantially new to this genre? The answer is a resounding Yes. The book’s subtitle, “An Anthology of Poetry and Medicine,” could be loosely applied to the earlier collections, but A Body of Work is the first to take the conjunction “and” quite seriously: not just an anthology of poems with the relevant subject matter, or poems written by medical practitioners, but rather an exploration of the relationship between poems and medical beliefs at the time of their writing.

Wagner and Brown situate poems in historical and cultural context by including excerpts from medical writings of the same period. These allow the reader to understand, at least to some extent, the mindset of the poet and his or her original audience. Because in each major section, poems and medical texts are arranged chronologically, the reader may also observe how medical understanding of a poem’s subject matter evolved over several centuries. This contextual approach creates a dialog between poetic and medical expression.

The Body of Work is divided into eight topical chapters: Body as Machine; Nerves, Mind and Brain; Consuming; Illness, Disease and Disability; Treatment; Hospitals, Practitioners and Professionals; Sex, Evolution, Genetics and Reproduction; and Aging and Dying. Within each section, poems are arranged chronologically, as are the excerpts from medical writings that follow. Consider the first chapter, which explores the metaphor of the body as machine. One of the first selections is by an anonymous 19th century poet who wrote:

Observe the wonderful machine,

View its connection with each part,

Thus furnish’d by the hand unseen,

How far surpassing human art! (p. 29)

In later poems this Enlightenment metaphor is variously affirmed, transformed, critiqued, and denied. For example, in the mid 19th century, Walt Whitman firmly rejected the mechanical man in “I Sing the Body Electric”: “And if the body were not the Soul, what is the Soul?” and “If anything is sacred, the human body is sacred…” (p. 33) In the early 20th century, D. H. Lawrence extolled the self-healing powers of body and soul, “I am not a mechanism, an assembly of various sections…” ( p.38) By the 21s century, poets were writing about their bodies with considerable irony, as in Jean Sprackland’s “Supraventricular Tachycardia.” The body is distinctly flesh, but not a machine, “my excitable cells don’t wait for the messenger.” (p. 68)

Similarly, medical elections in this chapter range from Julian Offray de la Mettrie’s explicit Man a Machine (1749) to Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), in which William James argued that such medical materialism is a “too simple-minded system of thought.” (p. 81)

Chapter 2, “Nerves, Mind, and Brain,” the evolution of poetic and medical perspectives on mental and nervous disorders. Take, for example, melancholy. John Keats (1820) spoke in the third person when he described melancholy as a spirit that may fall “sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud” on helpless man. “His soul shall taste the sadness of her might / And be among her cloudy trophies hung.” (p. 88) A century later, Edward Thomas, internalized melancholy, “What I desired, I knew not, But what e’er my choice / Vain in must be.” (p. 94) However, by the 21st century, poets have begun to assert their determination to fight and win at least small battles over depression, as Jane Kenyon wrote in “Having It Out With Melancholy.” Though “pharmaceutical wonders are at work,” she told her antagonist, “Unholy ghost, / you are certain to come again.” (p. 115) Medical writings from the 18th to early 20th century reflect a dramatic change in beliefs about the etiology of melancholy, from George Cheyne (1733), who claimed the illness was attributable to the damp climate, rich food, and sedentary lifestyle in England, to Sigmund Freud, who explained the disorder in purely psychodynamic terms.

The Body of Work contains countless such resonances between medicine and poetry that, from a medical humanities standpoint, give considerable added value to the more than 300 fine poems collected within.

However, the book does have one somewhat surprising deficit, given the editors’ avowed intentions. While contemporary poetry is numerically overrepresented (as is appropriate), the most recent medical writings date from 1919, aside from a brief excerpt from William Carlos Williams’ Autobiography (1948). Thus, most of the poems reflect dramatic developments in the understanding of illness that occurred in the last hundred years, while corresponding medical pieces are absent. Certainly William Röentgen’s “On a New Kind of Rays” (1905) and Joseph Lister’s “Illustrations of the Antiseptic Method of Treatment in Surgery” (1867) led to significant advances in the world of medicine, but haven’t similar developments in mid to late 20th century also radically influenced poetry about illness and healing?

Despite this caution, I strongly recommend A Body of Work to anyone interested in poetry about illness, or poetry and medicine, especially students of the health care professions and their teachers.