Dr Ian Walsh – Queen’s University Belfast, School of Medicine

email: i.walsh@qub.ac.uk

“Make our nervous system our ally instead of our enemy…… for this we must make automatic and habitual, as early as possible, as many useful actions as we can, and guard against the growing into ways that are likely to be disadvantageous to us, as we should guard against the plague.” James, W. (1992). Writings 1878–1899, p. 146. New York: The Library of America.

When patient safety has been compromised, what are the first comments to emerge? It’s virtually guaranteed that phrases such as “what were they thinking?”, “I don’t know what I was thinking…..” will be very much in evidence. This is a recognition that there is a fundamental error in thinking at play in the genesis of whatever risk has been exposed (hopefully before adverse consequences ensue).

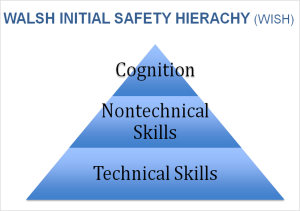

It is only recently that tribute is starting to be paid to the central issue of faulty thinking in the arena of patient safety. Until now, patient safety has been regarded and discussed using frameworks encompassing essentially two broad areas:

(1) Technical skills.

(2) Nontechnical skills

Technical skills are perhaps the easier to describe and grasp, as they essentially revolve around issues such as dexterity and hours of practice. Proficiency in this area can be assessed by a variety of means, such as via Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), Direct Observation of Procedural Skill (DOPS) and such. Teaching and assessment of technical skills proceeds in a usually stepwise fashion employing binary thinking and ranking. This generates essential objective data which lends itself well to quantitative analysis.

Nontechnical skills are a less well –defined group. They are largely concerned with communication, considered by most to be the key nontechnical skill of relevance in the clinical arena. Other such skills include (I’ve included communication as it remains “king”:

- Communication

- Teamworking

- Leadership

- Active Followership

- Situational Awareness

- Decision Making

- Assertiveness

- Prioritisation/Workload Management

- Conscientiousness

Nontechnical skills are somewhat inappropriately referred to as being “soft” skills, yet their absence of presence in poor quality are usually found at the centre of any Serious Adverse Incident in clinical practice. This skill set also sits alongside, and shares a lot of features with, the vastly important Human Factors group; which is thought to account for over two thirds of aviation accidents (the corresponding figure in healthcare is currently thought to be higher than this).

The difficulty with nontechnical skills and human factors lies in the perceived difficulty in teaching and assessing them. Coming from a largely technical skill – biased background in surgery, I was initially sceptical about the validity and reliability of teaching and assessing nontechnical skills. Together with experienced colleagues (all of whom notably also came from Team Technical), my belief was that such skills were not taught, but imparted. Learning by osmosis was considered the norm, if not the gold standard. My views have come to change in this regard; nontechnical skills can and should be taught to the same extent and arguably to a greater extent than technical ones. Communication can be video-recorded, analysed and archived. Team structure and roles (leadership, active followership) can be explained and practiced with simulated and standardised patients.

It is when one gets to individual nontechnical skills such as decision making ad self-awareness that challenges arise. We must turn to eminent authors in the fields of economics and behavioural analysis for assistance in this regard. As an example Daniel Kahnemann was awarded the Nobel Prize for his sublime work on cognition, fast and slow thinking. The General Medical Council have now come to recognise that such work should inform and be incorporated into undergraduate medical student teaching.

It’s one thing to demonstrate that nontechnical skills can be taught and assessed reliably, but can safe thinking actually be taught; and demonstrably so? I believe it can and recent data would seem to back this up. Introducing undergraduates to concepts of cognition (thinking, essentially) and metacognition (thinking about thinking) and self-awareness rapidly increased their ability to make correct and safe clinical decisions (Walsh et al, 2015). It remains to be tested if safer thinking can be sustained, but this is a promising start.

Encouraged by these findings, I now propose a different, inclusive view of the structure of Patient Safety and argue that it could apply to any arena where safety is of paramount importance. I’ve somewhat facetiously, yet succinctly named this “Walsh’s Initial Safety Hierarchy”, which then evolves into “Walsh’s Hierarchy of Metacognitive Safety” in the hope (apropos wish) that this will impart a degree of gravitas, if not admiration……..

Metacognition is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses”; I still prefer “thinking about thinking”). The salient feature of the WHOMS model is the overarching role of metacognition in safe practice.

References:

- James, W. (1992). Writings 1878–1899, p. 146. New York: The Library of America.

- Walsh IK, Spence A, Murray JM. Cognitive Reflection and Patient Safety. Presented at Association for the Study of Medical Education Annual Scientific Meeting, Edinburgh, July 2015.