Just because the the UK’s prime minister Boris Johnson and the Prince of Wales have had covid-19 doesn’t mean the disease strikes all people equally.

As with previous disasters throughout history, from the bubonic plague to the Grenfell Tower fire—the people who are hardest hit are those already disadvantaged. By the middle of May the pandemic had claimed over 33 thousand lives in the UK, but once again we see this is a depressingly familiar pattern repeated. People living in the poorest areas are twice as likely to die from covid-19 as those in the wealthiest areas.1 Black people are three to four times as likely to die compared to white people.2,3 Men in low-skilled jobs are four times more likely to die than professionals.4 It is clear that we are not “all in it together” and the less privileged in society are suffering the brunt of the damage.

Crises such as the pandemic are a stress test of the systems that aim to protect the worst off in society, demonstrating the shortcomings of those systems, revealing the unequal distribution of exposure, vulnerability and consequences. These crises send shock waves through society, exposing existing vulnerabilities leading into cycles of consequences, from the initial deaths from the disease, to the economic and social repercussions of control measures. So far, we have only seen the first wave of impacts and the inequalities generated are likely to be amplified through subsequent waves.

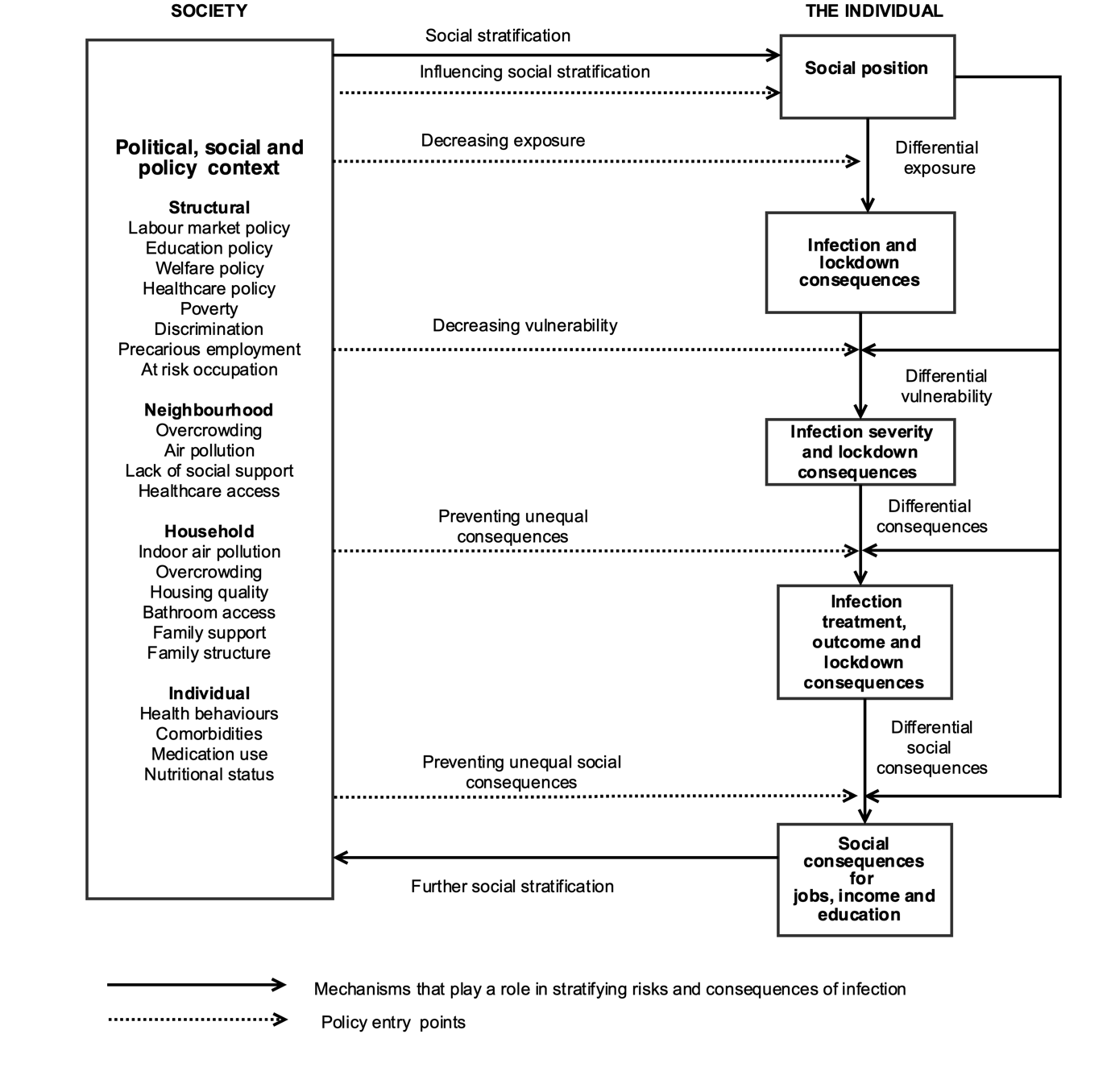

We need to learn from the existing wealth of knowledge on health inequalities to understand how these covid-19 related inequalities are generated in order to prevent them. The Diderichsen model (figure 1),5,6 which has been highly influential in health inequalities research, provides a crucial framework for understanding how inequalities are likely to evolve during the pandemic, and when and where we can intervene to prevent the health divide further widening.

Firstly inequalities occur due to differential exposure, both to the infection and to the unintended consequences of social distancing and lockdown.7 How much of the observed inequalities in health outcomes are explained by greater exposure of more disadvantaged groups to the virus because of where they live or the nature of the work they do? The social spaces that people are forced to inhabit as a result of poverty makes them more likely to be exposed to infection. Many low-paid jobs involve close personal contact—health and social care workers, shop and food outlet assistants, factory-floor workers, the gig economy. Living conditions for low-income groups may be more cramped and over-crowded, and neighbourhoods more densely populated. Differential exposure may be an important reason for these inequalities, but not the whole picture.

Secondly, inequalities are generated by ‘differential vulnerability’. Whether exposure to the virus leads on to illness and complications may depend heavily on other factors which make a person more vulnerable to the infection.6 We know, for instance, that rates of multi-morbidity and poor nutritional status are higher in more disadvantaged groups than in their more affluent counterparts and that long-term health conditions and disability set in at younger ages.8 Furthermore we have seen differential running down of public services in different localities over recent years, impacting the capacity of health and social care systems to respond. These vulnerabilities at an individual and area level interact with covid-19 risk to multiply adverse effects for disadvantaged groups.

Thirdly inequalities arise due to the differential consequences of covid-19 and control measures. There is already evidence of people in more precarious positions in the labour market being hardest hit by the shutdown of businesses and the lack of ability to work from home.7 The long term consequences could be devastating for already disadvantaged groups in terms of unemployment and likelihood of getting another job, with uneven long-term health effects, including on mental health. The unintended consequences of the lockdown are disproportionately affecting poor children, disrupting early child development and schooling, increasing hunger, mental health problems and the risk of abuse, neglect and non-accidental injury.9 These adversities will have an impact on the long term health of a generation unless appropriate action is taken.

None of this is inevitable, and the unequal impacts of the pandemic can be prevented, through evidence informed action at each of the pathways outline above. That requires research that unpicks the mechanisms of differential exposure, vulnerability and consequences, identifying the most effective policy entry points to tackle the aftermath of covid-19 and make preparations for the future.

Although the pandemic is caused by a virus, the inequalities it generates have social causes, and it will only be through the “organised efforts of society”10 that they will be prevented.

The pandemic arrived in the UK at a time when inequalities were already increasing,11-12 exposing underlying vulnerabilities, that are a consequence of years of austerity. Urgent action is now needed to prevent a further dramatic increase in health inequalities following this crisis.

Margaret Whitehead is W.H. Duncan Chair of Public Health in the Department of Public Health and Policy and Systems at the University of Liverpool, UK

Ben Barr is Professor in Applied Public Health Research in the Department of Public Health and Policy and Systems at the University of Liverpool, UK. @Benj_Barr

David Taylor-Robinson is Professor of Public Health and Policy in the Department of Public Health and Policy and Systems at the University of Liverpool, UK.

Competing interests: none declared

References:

- Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation – Office for National Statistics (accessed May 4, 2020).

- Rose TC, Mason K, Pennington A, McHale P, Taylor-Robinson DC, Barr B. Inequalities in COVID19 mortality related to ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation. medRxiv 2020; 2020.04.25.20079491.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by ethnic group, England and Wales – Office for National Statistics (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, England and Wales: deaths registered up to and including 20 April 2020 – Office for National Statistics (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Diderichsen F, Evans T, Whitehead M. The social basis of disparities in health. Chapter 2 in Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, With M. (eds). Challenging inequities in health: from ethics to action. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Diderichsen F, Hallqvist J, Whitehead M. Differential vulnerability and susceptibility: how to make use of recent development in our understanding of mediation and interaction to tackle health inequalities. Int J Epidemiol 2019; 48: 268–74.

- Douglas M, Katikireddi SV, Taulbut M, McKee M, McCartney G. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid-19 pandemic response. BMJ 2020; 369. DOI:10.1136/bmj.m1557

- Dugravot A, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, et al. Social inequalities in multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and transitions to mortality: a 24-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. The Lancet Public Health 2020; 5: e42–50.

- United Nations. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on children – United Nations

- Acheson SD, Security D of H and S, Britain G. Public Health in England: The Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Future Development to the Public Health Function. Chmn. Sir D.Acheson. London: Stationery Office Books, 1988

- Taylor-Robinson D, Barr B, Whitehead M. Stalling life expectancy and rising inequalities in England. The Lancet 2019; 394: 2238–9.

- Whitehead M, McInroy N, Bambra C. Due North Report of the Inquiry on Health Equity for the North. UK: University of Liverpool and the Centre for Economic Strategies 2014 (accessed March 27, 2017).