How can doctors work productively with patients, and what is the impact of doing so?

The clinician’s perspective

In 2015, as part of Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust’s new approach to investigating serious incidents, we decided to run a weekly Patient Safety Summit meeting to review newly declared serious incidents and to identify immediate learning that could be shared within the organisation. This replaced the former monthly retrospective “Learning Lessons” meetings which reviewed completed incident reports.

Summit meetings are held weekly for one hour at each of the Trust’s two hospitals and are chaired by the medical director or chief nurse. All hospital staff are invited to attend and issues arising from a recent adverse incident are explored. The meeting starts with everyone agreeing that the discussion will be confidential, but open and honest; and, most importantly—that all questions are welcome. The patient whose case is being discussed is referred to by their first name. Some staff found this a challenge at first, but we find it helps remind everyone that we are talking about something that has happened to a real person.

At the end of the meeting there is an expectation that staff take the questions asked at each summit back to their own clinical area and ask: “Could this have happened here?” and, “How could we prevent it?”

In addition, a safety bulletin is sent out to all departments, highlighting learning points which are prepared by the Quality and Safety Team. We plan to audit the distribution of the safety bulletin and test how far the learning has spread.

In August 2015, ten weeks after the inception of these meetings, we decided to introduce a key missing voice—that of a patient. This coincided with a drive from our new medical director to involve patients in all our quality and safety initiatives. We invited Sara Turle, a patient who has been working with the Trust since 2014 in a voluntary, unpaid capacity. She is a member of our Patient Partnership Council, a group of eight lay and two staff members together with four Trust representatives, who are charged with providing the Trust with independent and objective recommendations and support aimed at enhancing patient experience. The Council reports to the Trust Patient Experience and Engagement Group, part of the quality governance system.

Initially there were concerns about including a patient in our discussions. Clinicians can find it hard enough to discuss errors between themselves, let alone with a patient in the room. We worried that it would be saddening and frustrating for a patient to hear about another’s poor experience and at times catastrophic outcome. This was discussed between the medical director and Sara, who is involved on a voluntary basis, ahead of her agreeing to be involved, with follow up meetings for her to share any concerns or worries she had. These initially centred on how staff would react to her—a patient at the very heart of hearing where things go wrong—and what would she be able to contribute?

The impact of including a patient

Having a patient in the room has changed the way we look at serious incidents. When Sara started coming to the meetings she noticed that the dialogue was hierarchical and dominated by closed questions from senior doctors and nurses. Over time, the conversation has changed and become truly participatory. Seeing Sara ask questions and challenge answers has empowered junior members of staff to do the same. It’s also spurred clinical and managerial staff to think outside of their traditional professional boxes and really question how the system could be improved. Sara has helped broaden our perspectives by always asking how the patient, or their family, could have been more involved in their healthcare.

Staff members welcome having a patient voice in the room, and miss it when it’s not there. At one recent meeting where Sara could not attend, a doctor said: “what would Sara have asked here?” A survey of clinical staff attending the summits showed that clinical staff have found that having a patient present helps them frame their questions and answers better.

The patient’s perspective

I was asked to join the Patient Safety Summits by the medical director, whom I had got to know through other initiatives and forums I was participating in.

I think it was absolutely the right time for the Trust to take patient partnership to this new level, and finding that right time has, I believe, been key to the success of it.

I have seen staff recognize that they all, whatever their role, have a key part to play in safety. I have also seen how staff are genuinely affected by the experience of adverse events and want to improve and learn from it. When clinicians talk with a patient present, it helps normalize the invaluable, necessary discussions that lead to sustainable improvement.

Patient complaints are also discussed at summit meetings. One memorable example involved a discussion around a family who thought that more could have been done to save a relative who died after an unsuccessful attempt at resuscitation. I asked whether family members were present during the CPR and it became clear that in this case, the staff had not been following established best practice guidelines. It was clear that there was an assumption in the room that this would have been followed, but it was only when I asked the question that it came to light. Thirty minutes after the summit ended, a trust-wide notice had been distributed to ensure all members of staff were aware of current national best practice guidelines.

Outcomes

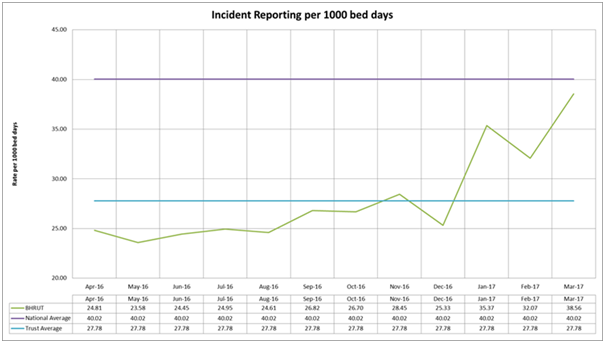

The patient safety summit has been part of the Trust’s wider strategy to instil a patient safety culture. Weekly discussion and reporting of serious incidents at both hospital sites has shown that staff see that reporting is taken seriously and acted upon. We have no evidence that having a patient present has had any impact apart from positive verbal comments of colleagues and seeing a culture shift which has led to an increase in reporting (see figure below). We believe that patient involvement has been a contributing factor in this.

Support and training for more patient partners is necessary to increase the number of patients involved. We need to involve more people to ensure long term sustainability. Developing our network of patient partners to help provide that support will be essential. Our newly formed Patient Partnership Council will help with this.

Attendance by staff at the weekly summit meetings is good; between 25 and 50 staff attend at Queen’s hospital, and between 15 and 25 staff attend at King George hospital. We have now asked a rotation of senior clinical staff to chair the meeting. In the future, it is our aim to have patient partners chair the summits as well.

Future direction

We have learned that a patient voice can make our lines of inquiry into incidents and complaints much richer and deeper than they otherwise might be. Future plans involve having patient partners sit on individual serious incident investigation panels to help ask the sort of questions that mean we really get to the root cause of our incidents.

By involving patients we believe we are creating a culture of open and patient-centred care. How can we measure that? It’s hard to say, but by starting to ask really simple questions without use of jargon, we are making patient safety “business as usual”. We know we are at the start of a long journey, but it is only by taking that path with patients and staff side-by-side that we can really start to move forward and have a measureable impact.

For any Trust considering involving a patient partner in patient safety initiatives we would advise identifying and working with a trusted, experienced patient partner. It’s also important to ensure they know what is entailed and are supported to participate fully.

Sara Turle is a patient partner at Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Sara Turle is a patient partner at Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Andy Heeps is associate medical director (Quality Improvement) and consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at Barking Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Andy Heeps is associate medical director (Quality Improvement) and consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at Barking Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Competing interests: Andy Heeps is a Health Foundation Generation Q Fellow. Sara Turle: none declared.

We hope this piece will encourage others to write about their own initiatives. The BMJ welcomes suggestions for articles or submissions for the series which should be sent to Cat Chatfield (cchatfield@bmj.com). The articles should be co- written by patients and health professionals. The aim of these articles is to raise awareness of joint initiatives, draw out lessons on how to work productively with patient partners, and flag the impact of doing so.