Milton Keynes was established as a “new town”, to relieve housing congestion in London, 50 years ago on 23 January 1967, an event that I did not think worthy of inclusion in my list of scientific anniversaries in 2017. However, the name of the town has medical resonances.

Milton Keynes was established as a “new town”, to relieve housing congestion in London, 50 years ago on 23 January 1967, an event that I did not think worthy of inclusion in my list of scientific anniversaries in 2017. However, the name of the town has medical resonances.

Milton Keynes, which now has around 250 000 inhabitants, was previously a village with a history that can be traced back to the Bronze Age, with evidence of human habitation in as early as 2000 BC. At the start of the 19th century it had a population of about 20 000. Its name comes from a shortened form of the Duchess of Cambridge’s maiden name, Middleton, “ton” meaning an enclosure or settlement, and Cahaignes a town in the French department of Eure in Normandy. The Cahaignes family came over with William the Conqueror and later settled in Buckinghamshire. Their name was derived from an old Celtic word meaning a juniper. The same name occurs in the Cornish town of St Keyne, named after its patron saint, one of the daughters of the legendary King Brychan of Wales. The village has a well the amusing properties of whose water have been immortalised in a poem by Robert Southey.

The name “juniper”, the common English variety of which is Juniperus communis, is a direct steal from the Latin name of the shrub, iuniperus. In French this became genièvre, genevre, geneivre, or genoivre, and in Dutch genever, nowadays jenever, from which we get our name for the spirit that is flavoured with a volatile oil of the juniper, gin. Other species include Juniperus sabina, Juniperus oxycedrus, Juniperus phoenicea, Juniperus virginiana, and Juniperus recurva. The origin of the name “sabina”, common name savin, is unknown, but I conjecture that it may be connected with the Latin silva, a wood. Cade oil, from Juniperus oxycedrus, prickly cedar, contains phenols, and local application reportedly caused convulsions, acute pulmonary oedema, renal failure, and hepatotoxicity in a neonate with atopy, and fever, hypotension, renal failure, and hepatotoxicity in a man who drank some.

Juniperus communis, with berries in different stages of ripeness

In A Modern Herbal (1931), Mrs Grieve writes that oil of juniper is used “as a diuretic, stomachic, and carminative in indigestion, flatulence, and diseases of the kidney and bladder. The oil mixed with lard is also used in veterinary practice as an application to exposed wounds and prevents irritation from flies.” She also describes its use “as a stimulating diuretic in cardiac and hepatic dropsy”. In his diary for Saturday 10 October 1663 Samuel Pepys described using juniper water for constipation, on the advice of his colleagues Sir J[ohn] Minnes and Sir W[illiam] Batten.

In her catalogue of Irish festivals, The Festival of Lughnasa (1962), Máire MacNeill says that if Brigid does not visit your house on her saint’s day, Lá Fhéile Bríde, coming soon on 1 February, to bestow her blessings as winter turns to spring, you should bless the house yourself (the word MacNeill uses is “sain”, literally to make the sign of the cross) by burning juniper twigs, to make reparations “in case any offense has been incurred that has kept the saint away.” Juniper was also used in this way as a fumigant to ward off infection.

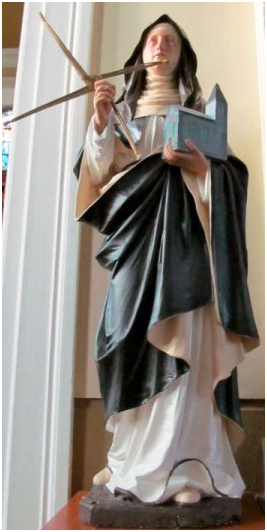

Image: Sr Brigid holding her characteristic cross, which has been used as the symbol of Raidió Teilifís Éireann

Mrs Grieve also says that juniper “imparts a violet odour to the urine, and large doses may cause irritation to the passages”, but she is coy about precisely which passages may be affected. In fact, juniper species, such as Juniperus sabina, savin, were used as abortifacients in ancient times and certainly cause abortion in cattle owing to the presence of the abortifacient isocupressic acid and metabolites such as agathic acid. According to Richard Mabey in his Flora Britannica (1996), giving birth under the savin tree was a medieval euphemism for miscarriage or juniper induced abortion. In view of this, it is a little surprising to find juniper listed in H E Wedeck’s Dictionary of Aphrodisiacs (1962), although there are few plants that are not mentioned in that eclectic text. Juniper’s abortifacient action, with the help of folk etymology, has led the savin tree in some places to be called the saving tree.

In Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition (2004), David Allen and Gabrielle Hatfield tell the story of an Oxford woman who wore sprigs of juniper in her boots, believing that as her feet became hot an active principle from the plant would be absorbed into her bloodstream, presumably having in mind its antifertility properties. The sprigs today reside in Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum. Perhaps she might have done just as well to drink some gin.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.